|

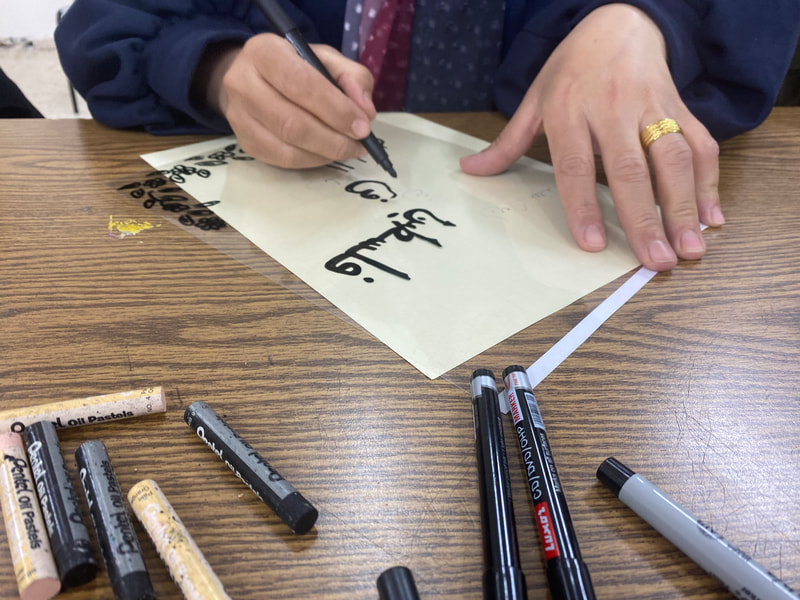

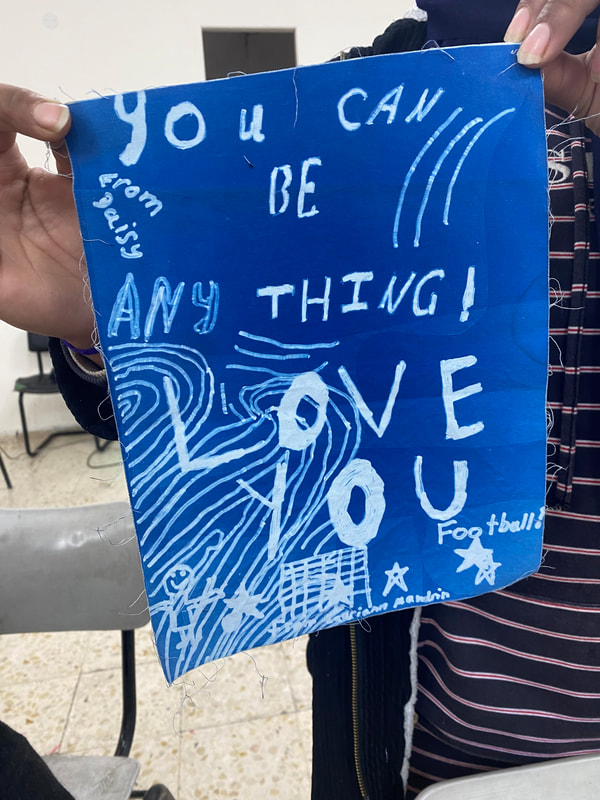

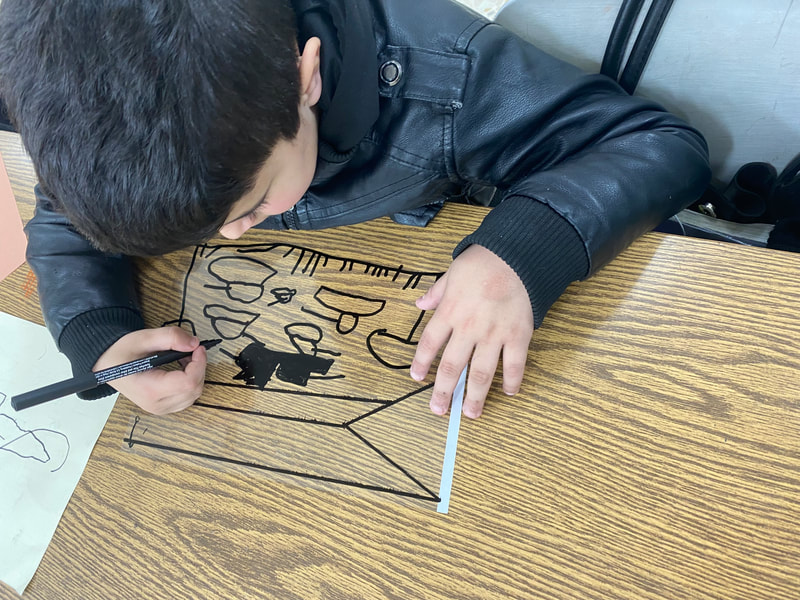

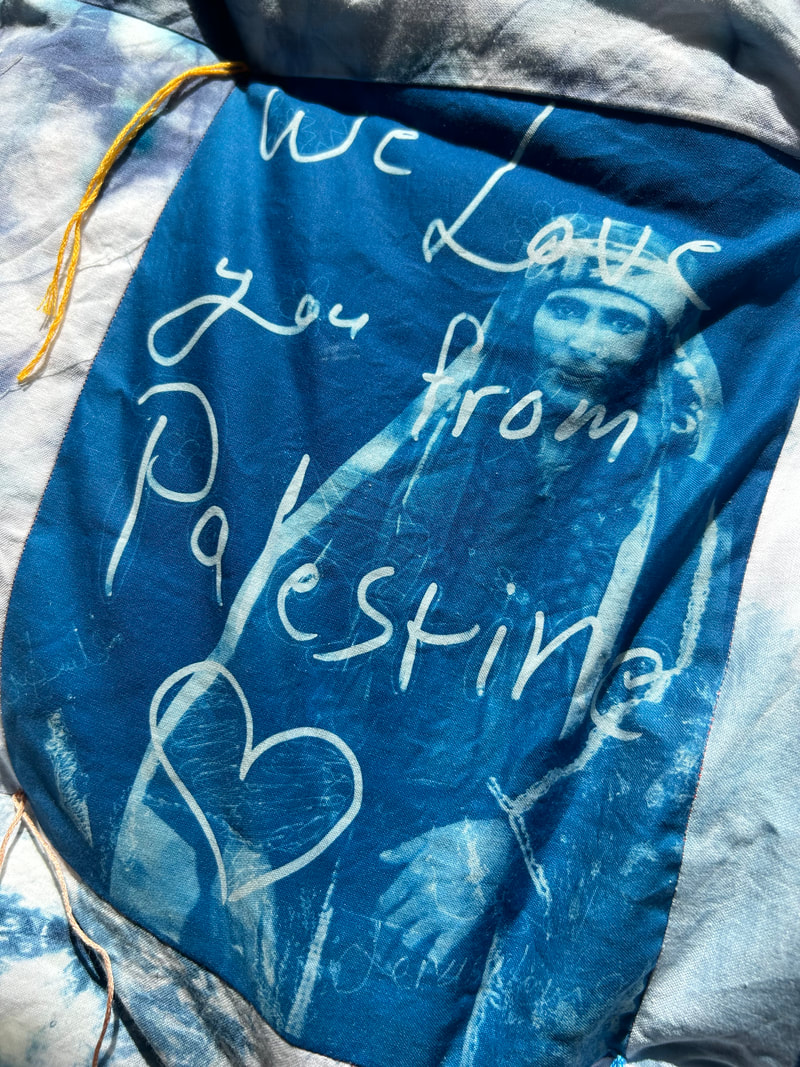

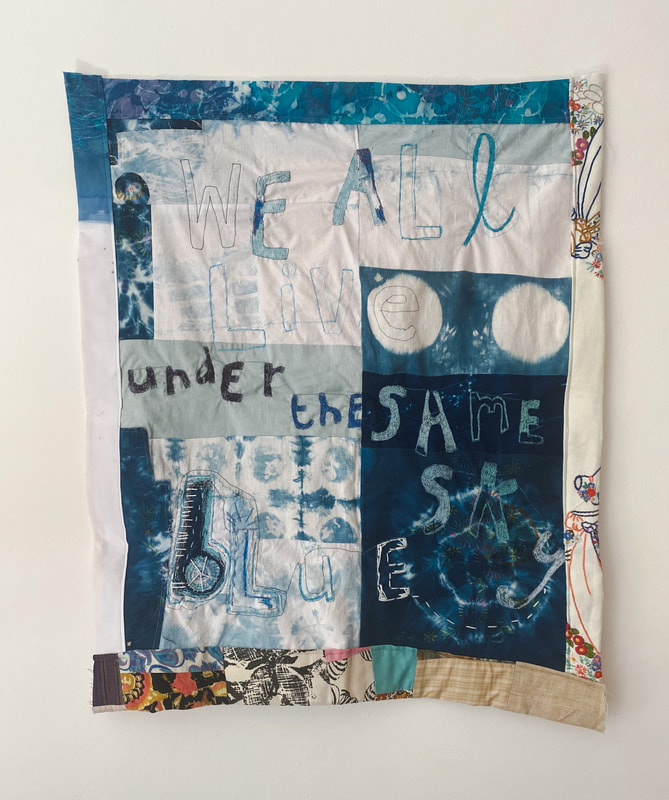

It’s been over a year since I posted a blog entry. More than a year. How can that time pass in such a blink? Time moves on effortlessly and we can only flow with it; accepting the things that get done and the many things that stay bound in the ether of our imaginations. Ideas that did not come to fruition, plans that stayed floating in the air around us. I must confess, I think it would have taken me even longer if it were not for the awful puncture of everyday life by the staggering events of Saturday 7th October – now dubbed Israel’s 9/11. The Middle East region is once again aflame with the release of much pent up pain. I was lucky enough to visit Israel and Palestine in March of this year. A long anticipated blog post has been in the making as I planned to share my precious photos of the magical time I spent there. Of the history I learned, the people I met, the food I savoured. The sights, sounds, scents of the ancient religious crossroads of Jerusalem; the vibe and hum of street art in Tel Aviv; the cute and cobbled streets of Bethlehem. We were all acutely aware that pain and trauma rumbled along the veins of the body of this land; that a peace and resolution lay somewhere far, far away. That things were tense and were liable to flare up in the violence of hurt hearts. But it was so breathtakingly beautiful anyway. The low pulse of fear could not eradicate the glory. We worked with a company called The Green Olive Collective to travel into the West Bank (part of the Occupied Palestinian Territories), visiting Ramallah and Bethlehem and winding past settlements as we drove the roads between. We gazed at the water tanks on the roofs of Palestinian homes due to their uncertain water supply; bullet scarred walls; Banksy artworks and the morphing street art along the Separation Wall. In Bethlehem, I was able to work with Palestinian women living in Aida Refugee Camp on a Comfort Quilt project. I arrived with cyanotype prints bearing messages of hope from the children I work with at The Mill Primary Academy. I returned to the UK with the women’s artwork which we then superimposed with old photos of Palestine using a UV lamp in the school’s art studio. Painstakingly, and with much love, we have stitched a squishy quilt patched with hand dyed swatches bathed in indigo hues. It is about to be shipped back to the camp to be enjoyed, although I am now concerned about whether it will ever make it to them. This seems utterly unimportant in the light of the many issues faced by Palestinians now trying to survive in the West Bank. As we ended the textile session at Aida and the ladies hugged me goodbye, I heard the unmistakable sound of automatic machine guns firing from within the camp. A woman smiled, looked me straight in the eye and said 'don't think about it'. I knew at that point that I was hearing the sound of training and preparation. Possibly they were getting ready for recent events. I shudder to my core at the thought.

But I do not take sides. It's a solemn promise to myself that I stay firmly only on the side of love and compassion, and that all humans deserve to be included in the gaze of this healing light. I have lived through division, sectarianism and the anguish of a deeply wounded society. It was all for nothing ultimately; we must share our space on this planet whether we like it or not. We must make space; within borders and within our hearts. It may sound wishy washy to those that prefer to raise their fists, but love actually is the cry of the strongest warriors of all.

0 Comments

This summer I was blessed with the opportunity to travel to Africa, along the way visiting my sons' beloved godmother Emma who lives and works in Kampala. As well as enjoying a safari and road trip around the west of Uganda, we were able to cross into Kenya and finally traverse to the island of Zanzibar. There is an African Proverb that states 'Travelling is Learning'. I find moving around the globe to be utterly life changing; jostling with enriching new cultures and connecting with a diverse array of people, foods, smells, ideas, philosophies, languages and attitudes. I travel to learn about history, politics, social anthropology, the arts; but most importantly, how all these things are connected and how they shape and affect one another. Absolutely nothing in this world exists in isolation, no event is separate and no-one is an island. It is a rich, interdependent biosphere with both tiny and catastrophic event constantly influencing future outcomes and decisions. I was lucky to soak up the African attitude of 'Hakuna Matata': the Swahili words for 'no worries'. Africans generally live in the moment much more than we do in the West; we are prone to trying to control the outcomes of our lives in a much more frenetic and demanding way. This doesn't mean that life on this huge continent is any easier, but approach is markedly different. Community, family, tribe and connection is everything and contrasts against the individualistic striving that I have felt the weight of growing up in the UK. Learning about the Ubuntu Philosophy has made a particular impression. Ubuntu is a Nguni Bantu term meaning "humanity". It is sometimes translated as "I am because we are". There are various definitions of the word "Ubuntu". The most recent definition was provided by the African Journal of Social Work (AJSW). The journal defined ubuntu as: A collection of values and practices that people of Africa or of African origin view as making people authentic human beings. While the nuances of these values and practices vary across different ethnic groups, they all point to one thing – an authentic individual human being is part of a larger and more significant relational, communal, societal, environmental and spiritual world. Video of our summer spent travelling across East Africa Of course, Africa is a continent that has suffered much under the weight of warlords, tycoons, conflict, and the devastatingly unstabilising effects of colonialism; an undermining of its structure that has left it vulnerable to the looting and systematic theft of its valuable resources. Uganda and other countries were literally concocted land borders, made up by UK, France and other Western countries in the Scramble for Africa.

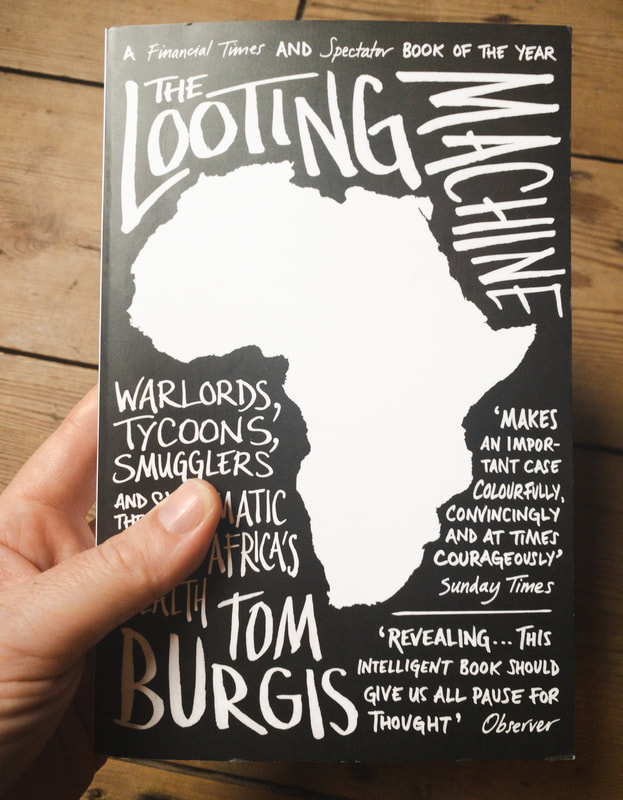

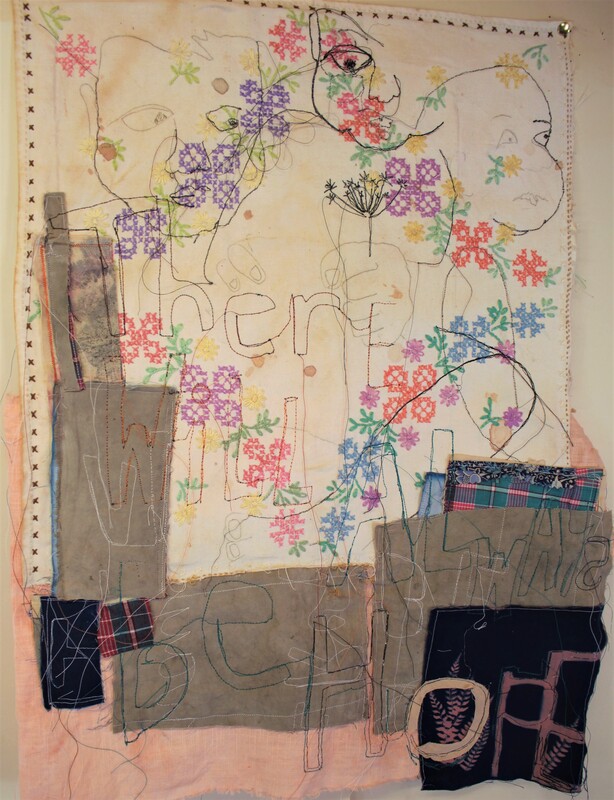

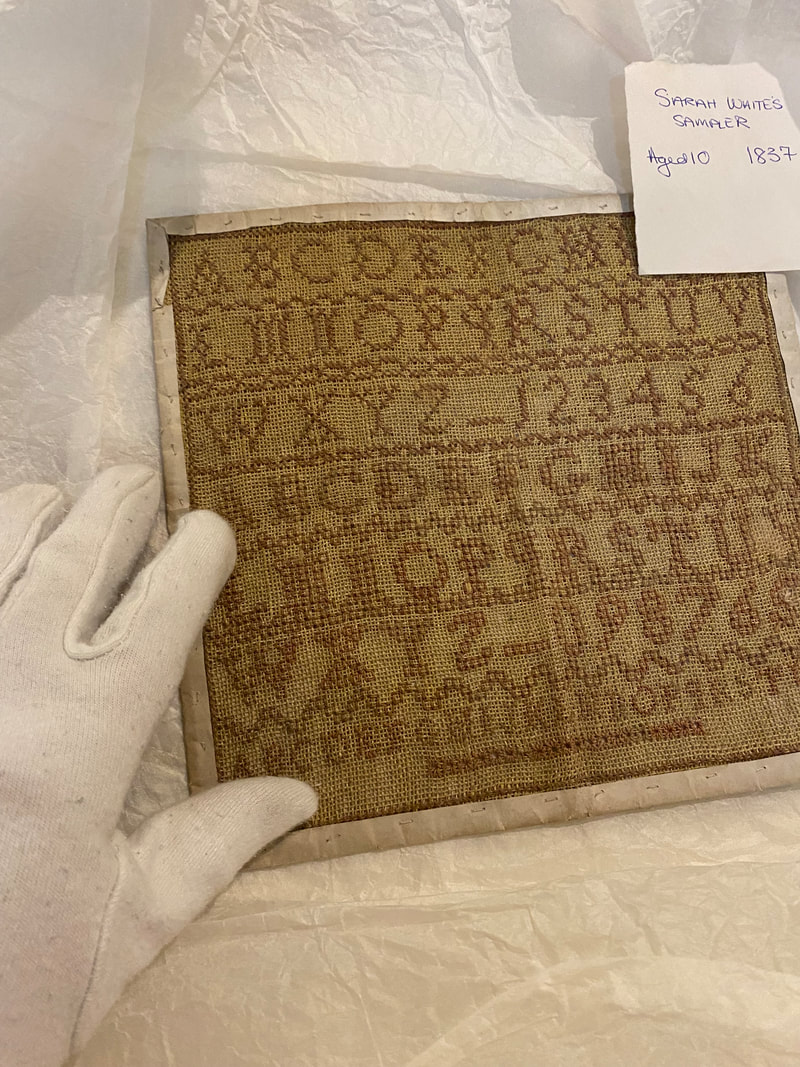

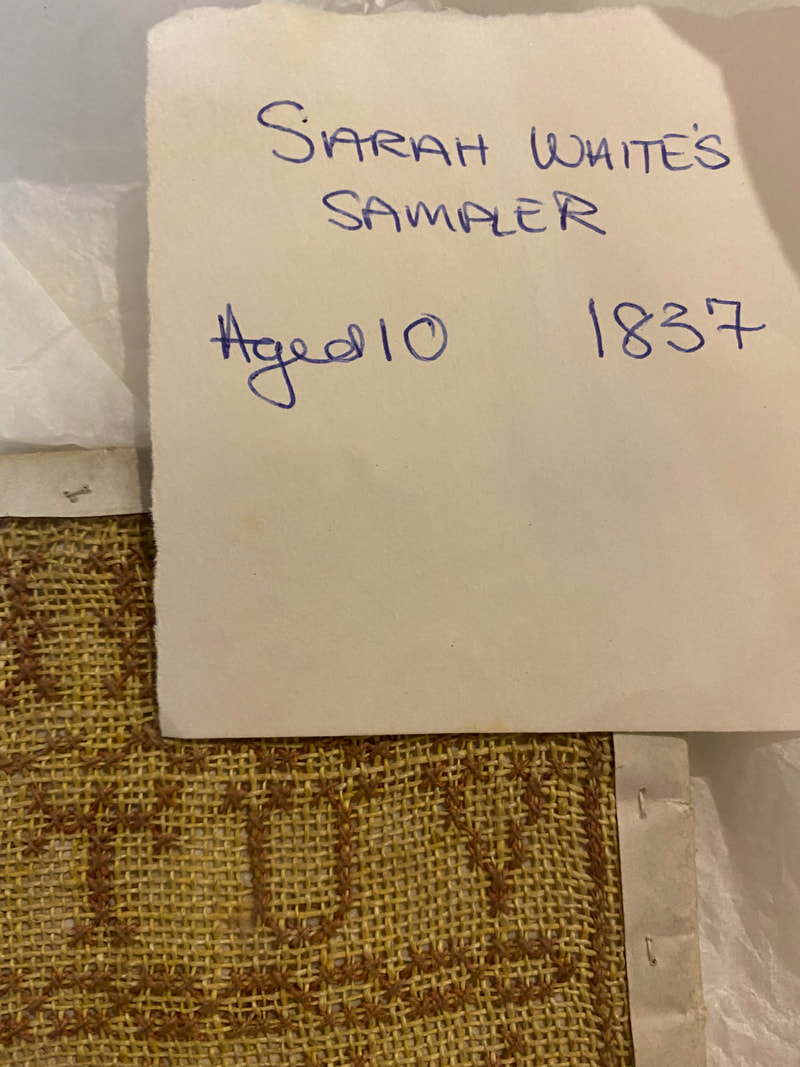

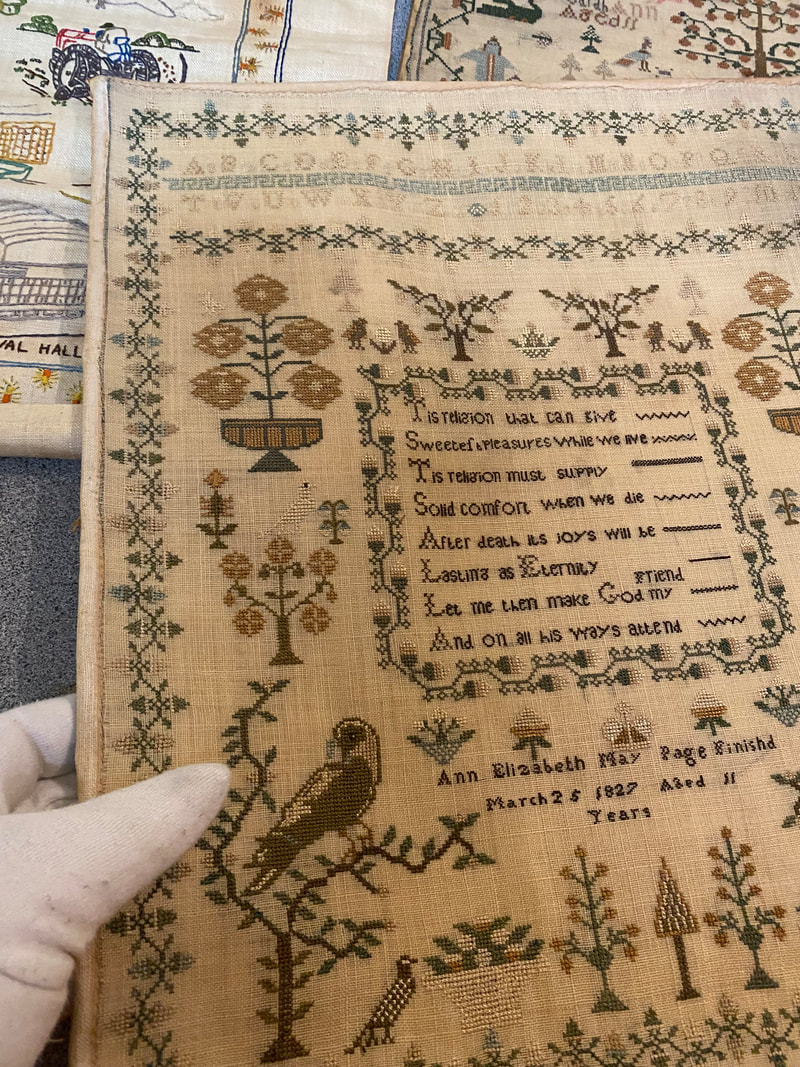

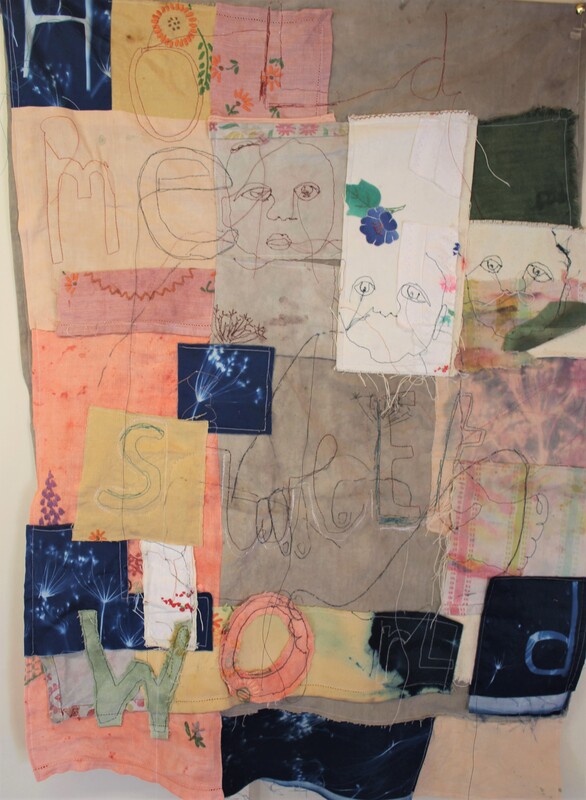

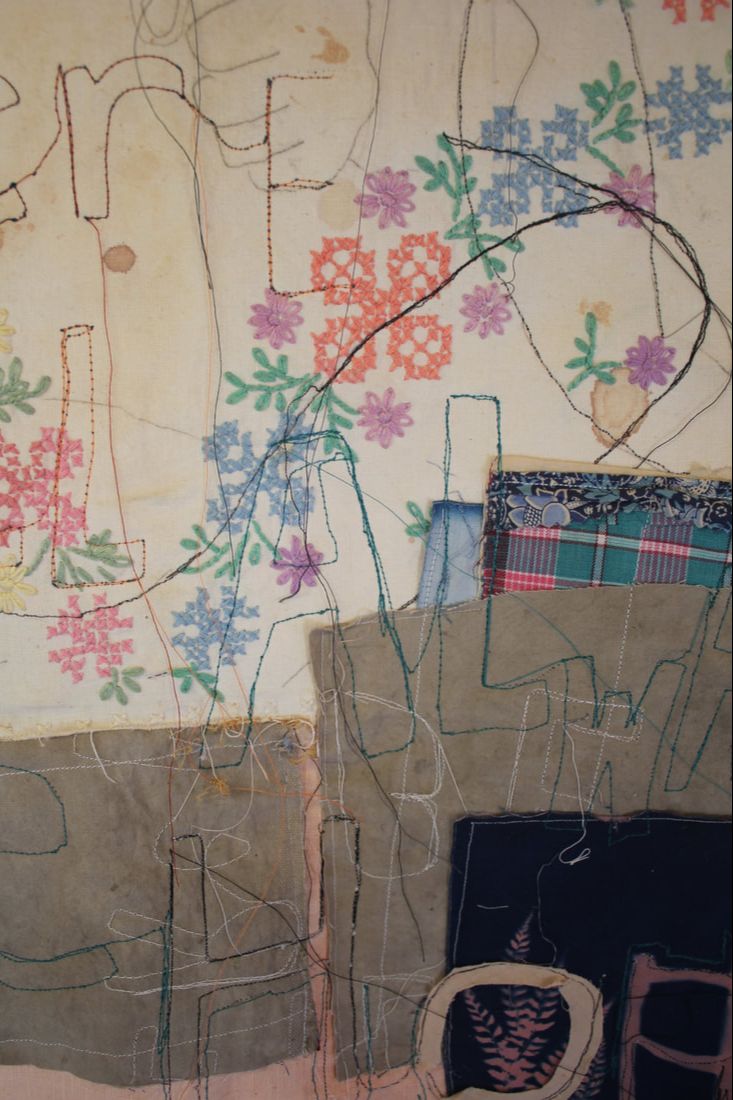

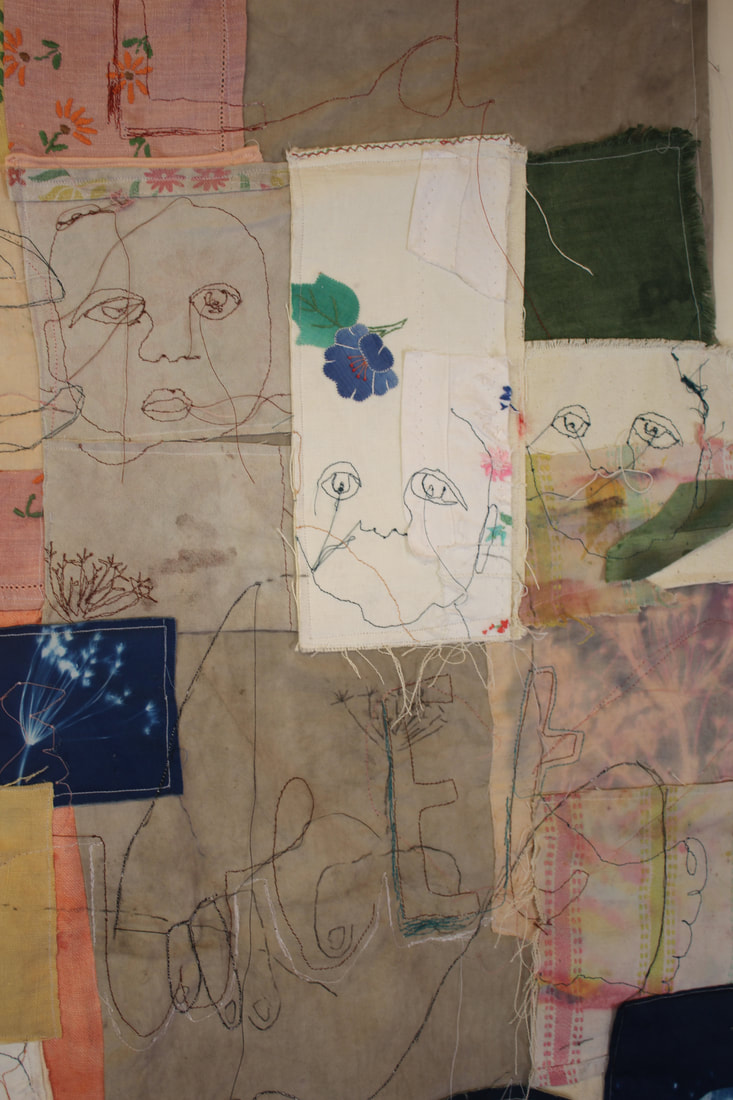

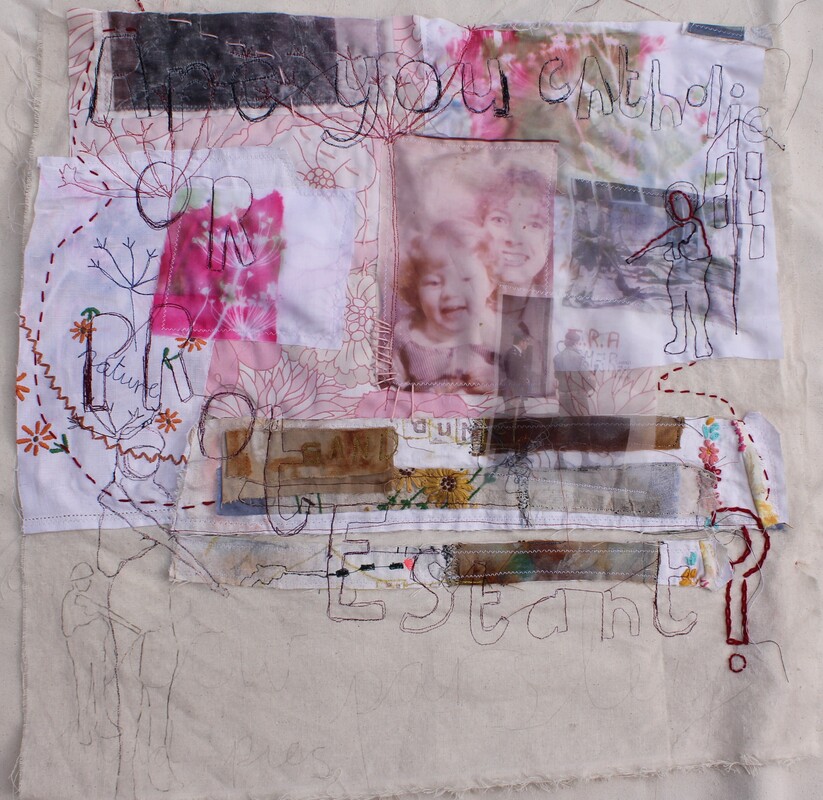

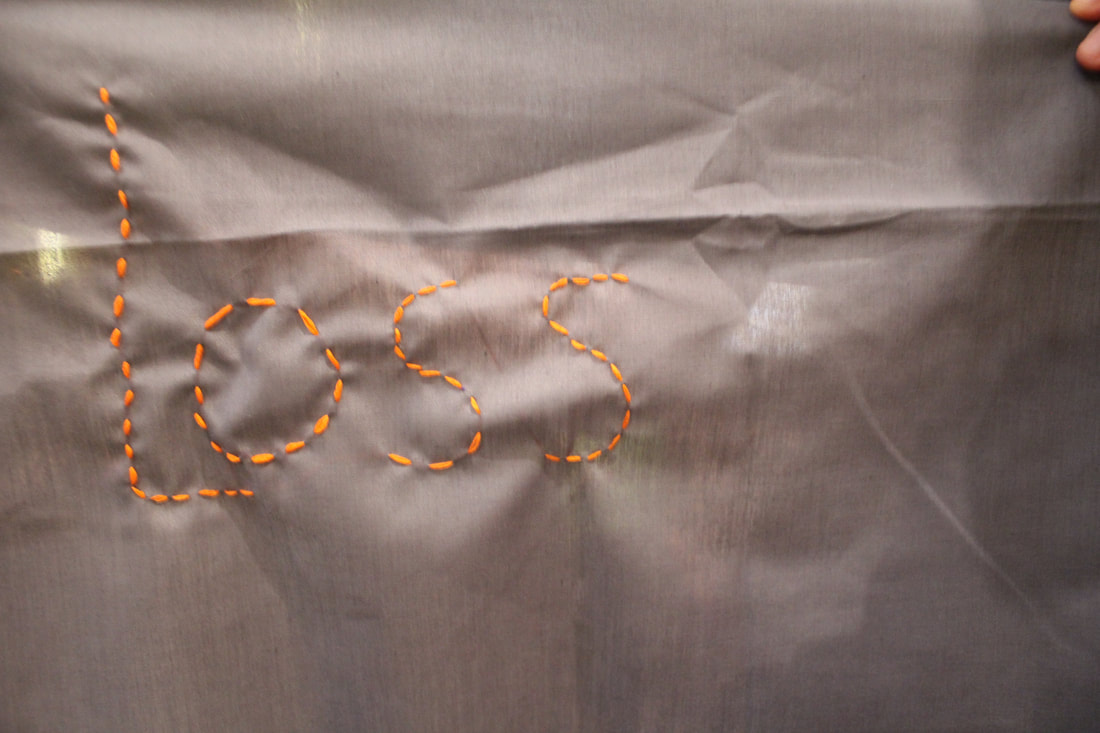

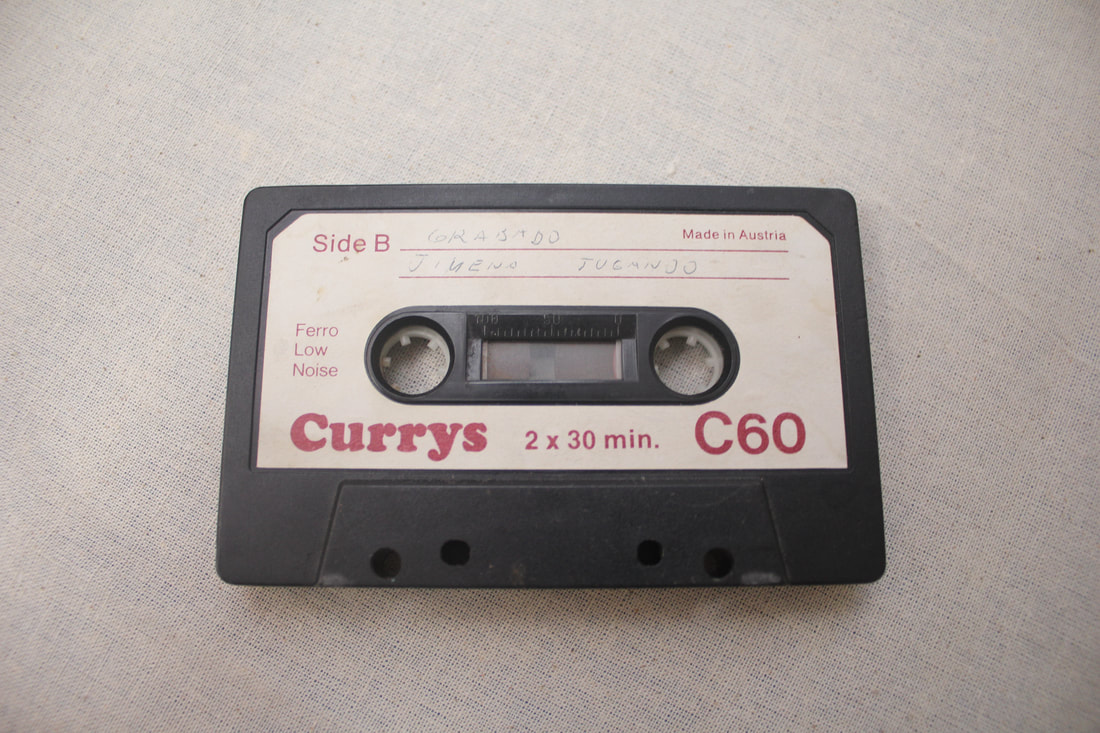

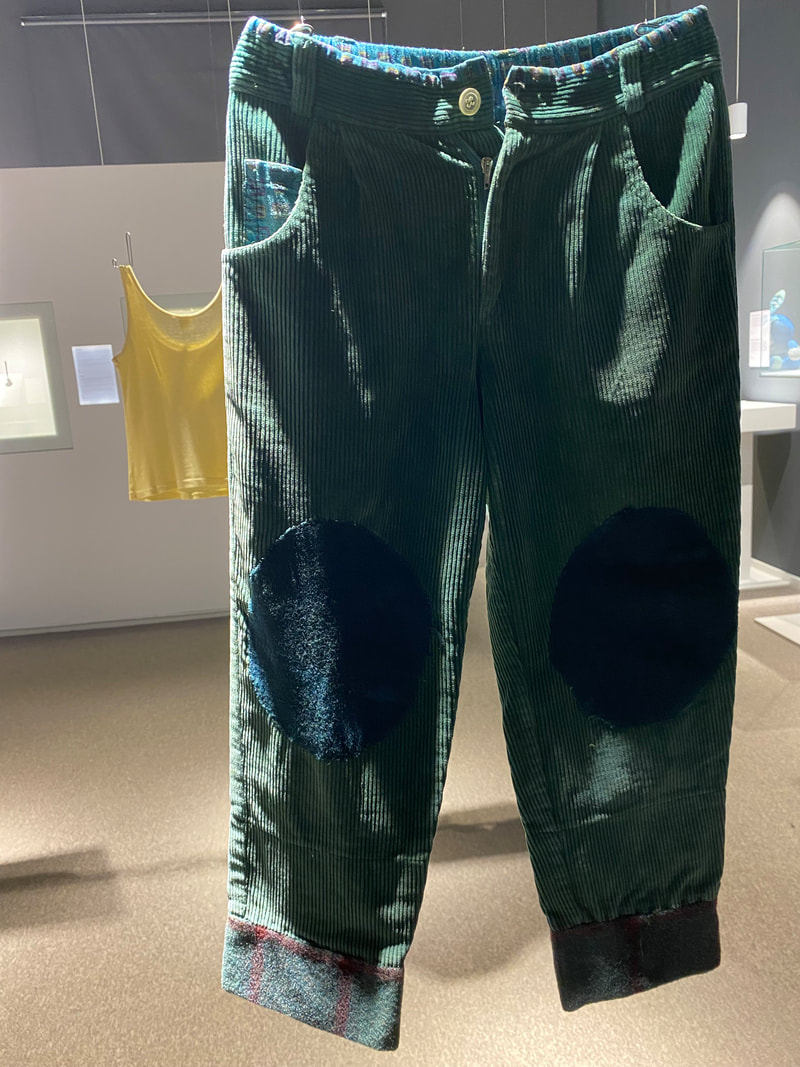

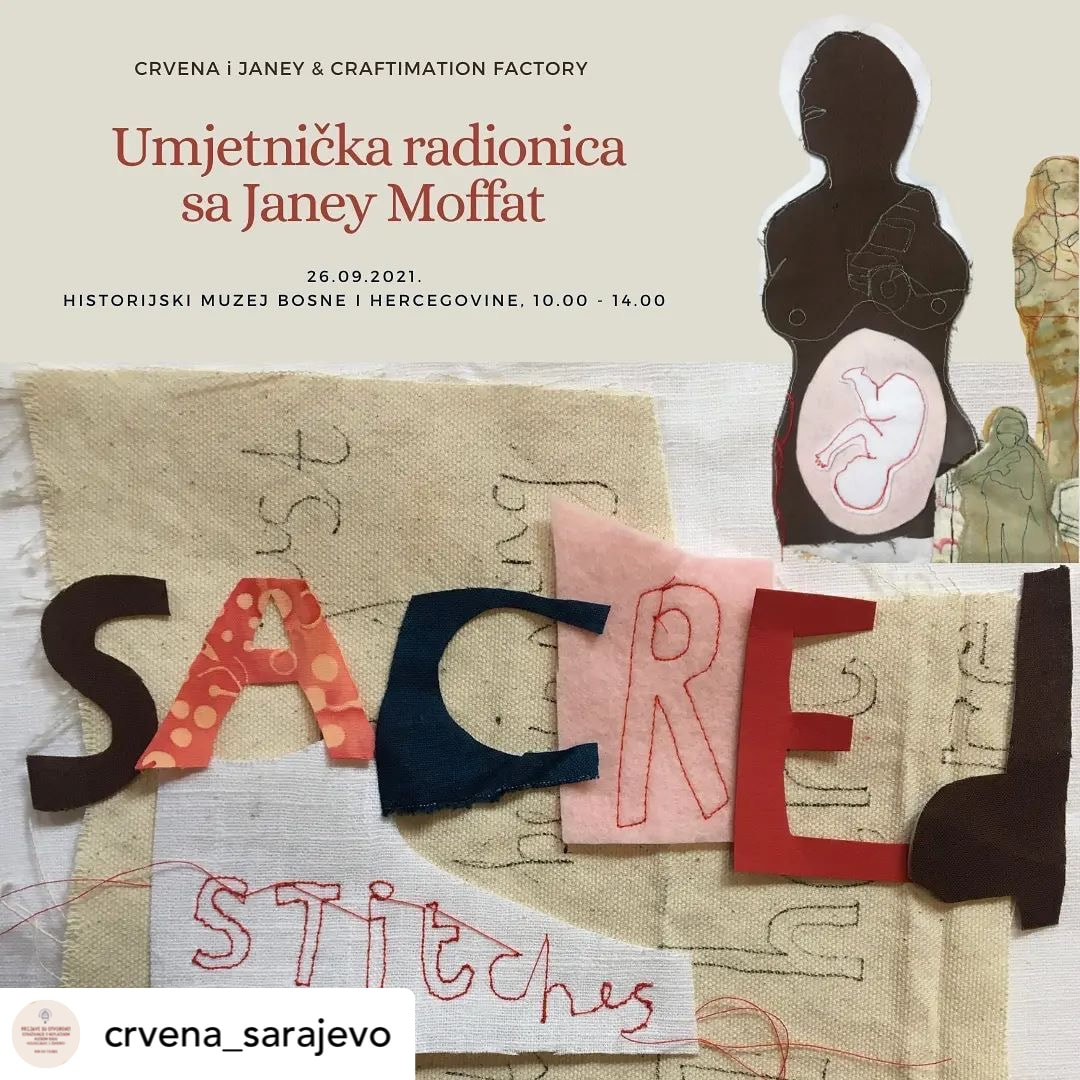

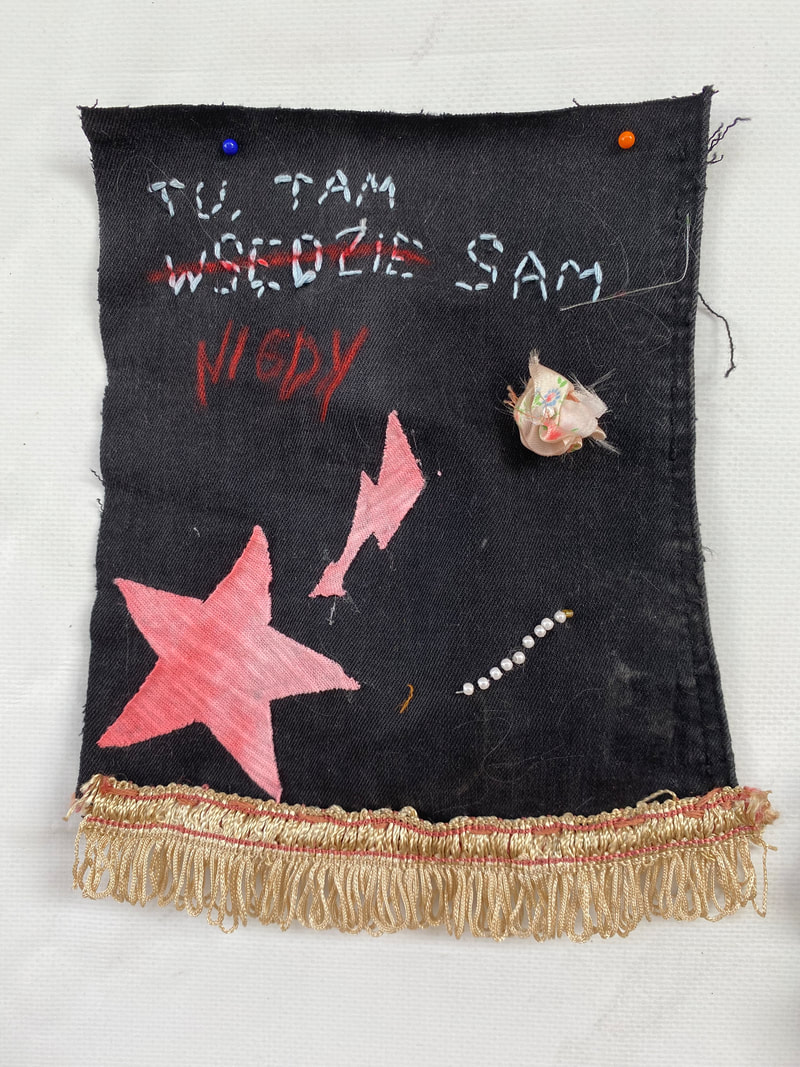

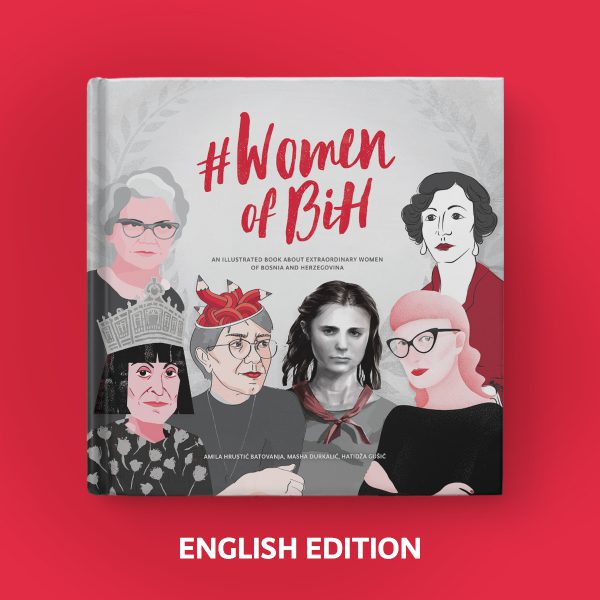

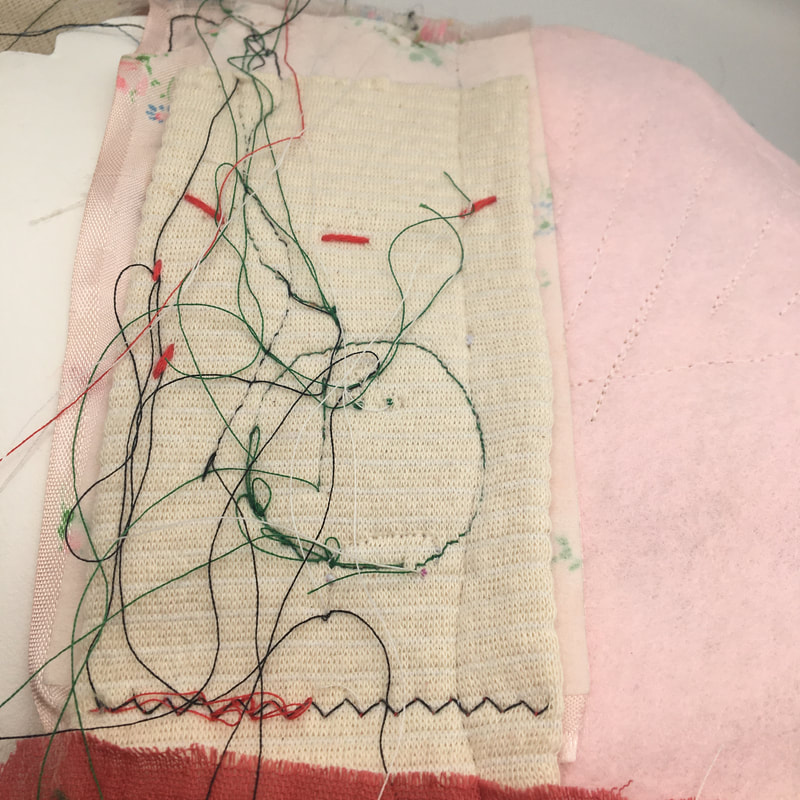

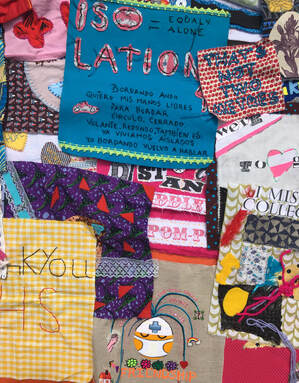

It is little wonder after centuries of control, coercion and dictation from outside forces, that figures such as Idi Amin and Robert Mugabe have been able to step into power. I think of The Troubles and how the precarious situation in Ireland gave birth to the heated opinions of Ian Paisley and Gerry Adams, and how the lines between politics and paramilitary tactics became increasingly blurred. When a country is unable to thrive on its own terms it can cause fractions and frictions that become a breeding ground for tension and violence. I am determined to further my learning about this beautiful land mass and am slowly making my way through 'The Looting Machine' by Tom Burgis; a book that I hope can deepen my understanding not only of Africa, but of how the struggle for power anywhere in the world can only lead to conflict and despair as we pivot away from the Ubuntu values of connection and belonging. Life plods along, the world seems to be going crazy in its wake. Since I last updated war has writ large on Ukraine and there are whispers of World War 3, Putin suddenly roaring up monstrously in front of us all like the mini tyrant he has always been. The heady days of our carefree pre pandemic ignorant haze seem so long ago. At that time we thought such challenges were mere history, lost to the echoes of time and something we would never have to face. Now we are all weighed down by the threat of danger, the gobsmacking rise in the cost of living, a pandemic that never seems to truly end, and a looming climate catastrophe that feels suffocating in its breadth. My childhood troubles and subsequent trauma all of a sudden seem to have been really good preparation for what is ultimately a tumultuous world. I no longer feel that ‘this only happened to me’ in ‘this place’ at ‘this time’. It’s all happening to everyone; everywhere. Even those who are ultra-rich, mind bogglingly buried in denial, or utterly optimistic, still have to live with reality creeping in around the edges. It seems so fortuitous – an utter blessing – that I have been writing this blog and developing a practice around the very idea that creating, making, and losing myself to the process can help me navigate choppy waters and difficult moments. Breathing in deeply the sacred of every day moments by watching cyanotype prints dance magically under the gleam of sunlight, coaxing wonderful hues from natural dyes, sorting through the nostalgia of vintage table linens. All of this helps to ground me firmly in the safety of the present moment. Throughout 2022 I’ve been helping to facilitate two wonderful textile projects: ‘Where Are You Really From?’ and ‘Bandage Me Better: Sacred Stitches’. You can read more about either of them in earlier posts, or at this link: www.janeymoffatt.com/bandage-me-better.html During the last session of ‘Where Are You Really From?’, hosted by Hastings Museum, we were treated to an up close study of a selection of beautifully stitched samplers and other textile works from the museum’s collection, items ranging from 70 to 200 years of age. I absolutely adored donning the prerequisite white gloves and becoming historian for the afternoon as I was allowed to gently handle each piece. It was utterly moving to hold the work of another who lived so long ago, examine their stitched name, age and date of completion. What struck me was the accuracy; a sharp reminder that textiles have been inherently associated with neatness and conformity – a tool in the taming of women across the decades. Mentally I compare these tiny careful stitches with my own messy, wobbly seams and loose hanging threads, feeling like I’ve somehow come up utterly short. I contemplate Sarah White, aged 10, poring over her sewing and wondering whether it was a source of joy or anxiety for her. This sampler is all that it left of her delicate human hand; I can only guess at what she felt, what she hoped for, what gave her joy. Whether she too listened to birds singing and felt a little leap of happiness, whether the sight of the sun setting brought peace to her being. I am lucky to live in an era when I can choose whether my stitches look neat or dishevelled; it’s a luxury to choose my loose sewing as an aesthetic expression. My shirking of neatness is the same reason I love cacti best of all the plants, and appreciate a grey, grim and gloomy sky. I am from a dark, gritty place and I will not banish the chaotic and uncontrolled from my life. Because to do so would be to banish life itself. It feels like an eternity since I’ve updated the blog; life has been that usual whirlwind of parenting, cleaning and juggling work commitments – but with Christmas, a gruelling work schedule and a good old bout of Covid thrown in for good measure. Just in case I was not quite busy enough! The last time I wrote was not long after my return from Sarajevo, a touching and illuminating journey to a beautifully nuanced place. Once back in Hastings, I was able to deepen my understanding of the situation in BiH by having Zoom conversations with Nedzad of CAN (a peace organisation) and Andreja from Crvena, who filled me in on the role of women across the former Yugoslavia, its break up, and throughout ongoing tensions. I was fascinated to learn how war cracks life open for women; they certainly suffer more from vastly increased incidents of rape and domestic violence. Yet simultaneously, somehow grim opportunities open up to them and they are sometimes able to take on roles previously only ever thought of for men. In 1942 the Women’s Anti-Fascist Front formed in Bosnia in the overshadowing crisis of World War 2, eventually gathering the support of some 2 million women. Women somehow eked out more space for themselves in otherwise devastating times, carving out the opportunity to emancipate themselves through resistance and revolutionary thinking. They would partake in a wide variety of activities, from knitting jumpers for partisans to carrying guns and hiding weapons. I learned from Nedzad that Bosnians still live under the shadow of the very real threat that fighting could break out again, revealing to me what seems totally obvious – war is not one isolated incident that comes and goes neatly within the dates we learn in school. War, conflict, oppression and everything that accompanies them, ooze out the sides and spread into the following generations for an unknown amount of decades, centuries even. Since I started writing this (a couple of months ago), we have the blistering conflict searing across Ukraine. Pockets of violence rumble in Afghanistan, Yemen, Palestine, Ethiopia, Libya, Syria – the list goes on. I hear whispers that the IRA continues to recruit in Northern Ireland. It’s on our doorstep. It’s everywhere. Amazingly, I learned that Roberta Bacic, the very woman who first uttered the words ‘Conflict Textiles’ to me, had a Yugoslavian father who made his way to Chile where she was eventually born. She was able to tell me about the Srebrenica Memorial Quilts; fifteen memorial quilts that commemorate relatives who died in the 1995 massacre at Srebrenica, BiH. Altogether, the quilts carry the names of almost 350 victims, and represent an extraordinary initiative by their relatives to keep their memory alive. The first memorial quilt was modelled on the AIDS Quilt, and woven in 2006 with assistance from Peace Fellow Yvette Barnes. Known as the Weavers’ Quilt, it carried the names of 20 massacre victims who had all been related to the weavers. Each quilt carries its own poignant story; the Teachers Quilt remembers teachers who lost their lives at Srebrenica. The 14th Memorial Quilt remembered 20 children under the age of 16 and was woven in white to symbolize the innocence of the children, while the 15th Memorial Quilt commemorated 20 women who were killed because they decided to stay with their husbands and other male relatives. BOSFAM then took all fifteen quilts to the scene of the massacre, for the July 11 reburials that marked the fifteenth anniversary of the massacre. The quilts hung along the side of the notorious former Dutch UN base, while families reburied another 755 victims. Mothers from Srebrenica carried memorial quilts to the Hague for the trial of Radovan Karadzic in 2008. Taken from The Advocacy Project website https://www.advocacynet.org/39189-2/ Textile artworks can be such a powerful tool for remembrance; they are powerful, hand wrought emblems that can bare our stories to the world. So often employed by women, stitching is an art form that is accessible to almost anyone; inclusive, communal and meditative in their formation. I’m delighted to be working with The Refugee Buddy Project, Stitch For Change and Jimena Pardo once more, this time in conjunction with Hastings Museum and Art Gallery on the project ‘Where Are We Really From?’ The question, often loaded with negative bias and sweeping assumptions, is being reclaimed in this project. From homeland to heritage, ancestry and culture, the work created explores our roots, stories and sense of identity. Patchwork pieces featuring precious photos printed on fabric, are being stitched on by Hastings people with experience of migration and seeking refuge, alongside the volunteers who support and advocate for them. Through a series of workshops, participants are sharing stories, reflecting on treasured photos, objects, images and words that will be included in their final textile artworks. So far, participants have shared moving stories about their escape from intolerable situations; families fleeing the Holocaust of World War 2 and more recent conflicts in Syria and beyond. Jimena, my fellow facilitator, shared about her arrival as a refugee from Chile's Pinochet dictatorship to the UK at the age of two. She brought the powerful image of a cassette tape - this humble item was used to communicate with family members back in Chile in a way that felt safe and uncensored. Jimena and her family members would record themselves talking and mail the tapes to their loved ones across the ocean. Ultimately, people are greater than war and conflict. Humans continue to survive and thrive in the most impossible of situations and war has not yet wiped us out. Now we must double our efforts to evolve beyond the need for greed, power, control, violence. 'Where Are You Really From?' will be on display during Refugee Week 2022 and as part of the Sanctuary Festival, which takes place in the museum grounds on Sunday 26th June. The Bosnian War; a long, complex, and ugly conflict that followed the fall of communism in Europe. In 1991, Bosnia and Herzegovina joined several republics of the former Yugoslavia and declared independence, which triggered a civil war that lasted four years. Bosnia's population was a multi-ethnic mix of Muslim Bosniaks (44%), Orthodox Serbs (31%), and Catholic Croats (17%). The Bosnian Serbs, well-armed and backed by neighbouring Serbia, laid siege to the city of Sarajevo in early April 1992. They targeted mainly the Muslim population but killed many other Bosnian Serbs as well as Croats with rocket, mortar, and sniper attacks that went on for 44 months. As shells fell on the Bosnian capital, nationalist Croat and Serb forces carried out horrific "ethnic cleansing" attacks across the countryside. Finally, in 1995, UN air strikes and United Nations sanctions helped bring all parties to a peace agreement. Estimates of the war's fatalities vary widely, ranging from 90,000 to 300,000. To date, more than 70 men involved have been convicted of war crimes by the UN. – Alan Taylor, The Atlantic Despite the pandemic still writ large, and with no small amount of trepidation, I recently deliberated on whether I should rebook a work and research trip to Sarajevo that had been planned before Covid struck us. With travel rules constantly morphing, I dreaded the prospect of being stranded in a dodgy hotel hundreds of miles from home, yet a small but loud part of me insisted that I needed to get back out into the world and embrace it. On 24th September I flew to Sarajevo via Vienna and landed exactly on time and with no hitches whatsoever. I had yearned to visit Sarajevo ever since a family holiday to Croatia that saw us taking a day trip into Bosnia & Herzegovina, taking in the sights of the beautiful city of Mostar. I was captivated instantly by a place that was worn around the seams, dishevelled by conflict yet boasting great pride and beauty. Riddled with scars and carrying a silent sorrow in its soul, I recognised at once a country that had endured yet survived. I adore this kind of worn out, harrowed loveliness way more than any ‘perfect’ tourist destination. Because it’s in this dilapidation where great stories live. I was lucky enough to connect with Crvena, a feminist organisation based in Sarajevo who had agreed to host me as I facilitated a textile workshop. They had organised for me to work in a sunny outdoor courtyard at the rear of The History Museum of Bosnia & Herzegovina, where I was surrounded by the leftover machinery of war; all sorts of cannons and other killing paraphernalia sat lazily in the sunshine whilst we worked around them. The evening before the workshop I met with the irrepressible Andreja of Crvena; she had given birth to a baby boy only two months prior yet was energetically organising and promoting the workshop. She took me to Caffe Tito, a nostalgic reminder of life in former Yugoslavia under President Tito, with photos and other objects from the socialist period. We chatted and swapped experiences of life as women, the searing inequalities that we face in our roles as mothers, how conflict shaped the lives of women. She told me how she and her mother had been forced to leave BiH as refugees for the relative safety of Croatia, the grief in giving up their comfortable life in Sarajevo to live in substandard conditions in order to be safe. The next day, with Andreja translating, the workshop went smoothly - me learning way more than any of the participants. They told me they were communists, and elaborated on how strong the feminist movement had been during the time of Yugoslavia. Andreja had previously devoted her time to putting together a small permanent exhibition that was housed in the museum. It displayed, along with other items, copies of the radical ‘New Woman’ magazine that had been published during the period. After the workshop I gazed at the items, wanting to know so much more of their story. Some of the participants at the workshop had been really young, born long after Yugoslavia had broken up and rearranged itself into new countries, long after the most recent war had raged. Yet they burned with Yugonostalgia and a passion for a time that they had never known. I couldn’t blame them. Capitalism has hardly brought us untold joy, so why wouldn’t they look to something else? I turned the idea of communism and its potential benefits over in my head. It was certainly food for thought. Read more about Crvena here: crvena.ba/ Learning about the nuanced and complicated history of the Balkans was therapeutic for me; it ensured that my own troubled story in Ireland felt less isolated and strange. I deepened the conversation by connecting with a couple of other people; a journalist called Orhan who had been a young adult during Yugoslavia, and who had fled to Turkey during the conflict, and a guide called Adis who was born in the last year of the war. Adis took me all over the city and I glimpsed the Tunnel of Hope, constructed between March and June 1993 during the Siege of Sarajevo, allowing food, war supplies and humanitarian aid to make its way into the city. He showed me Sniper Alley and the still pock marked buildings blighted by gunshot wounds, but also the dilapidated bobsleigh track made famous by the 1984 Winter Olympics (who could forget the world famous performance by Torville and Dean?), now covered with street art and political messages. And how did Orhan remember the period? The communism of Yugoslavia had failed he stated pragmatically, feeling that there had been a certain inevitability to it all, pondering over the Ottoman invasion centuries prior and reflecting how the conversion of many to Islam at this point had continued to influence tensions in the region hundreds of years later. Later, back at my AirBnB, I learned how women had formed their own resistance during the war by donning their best clothes and make up, even when they were forced to walk down Sniper Alley. Their attitude was one of defiance – if they were going to die, they were going to die dressed in their best. I watched footage of Miss Sarajevo on YouTube; contestants of the beauty pageant held in the midst of the besieged city had carried a huge banner stating ‘Don’t Let Them Kill Us’, with the moment immortalised in song by U2 and Brian Eno. I marvelled at how the women had held together the threads of a normal life in the midst of chaos and destruction, as I know women do the world over. Holding things together for their children, their wider families and communities. On the final day of my visit I stumbled across the book Women of BiH in a tiny store placed along a side street. I immediately purchased it, feeling instantly that I needed to know more about these pillars of strength, knowing that I would draw on their fortitude and grace in times of need.

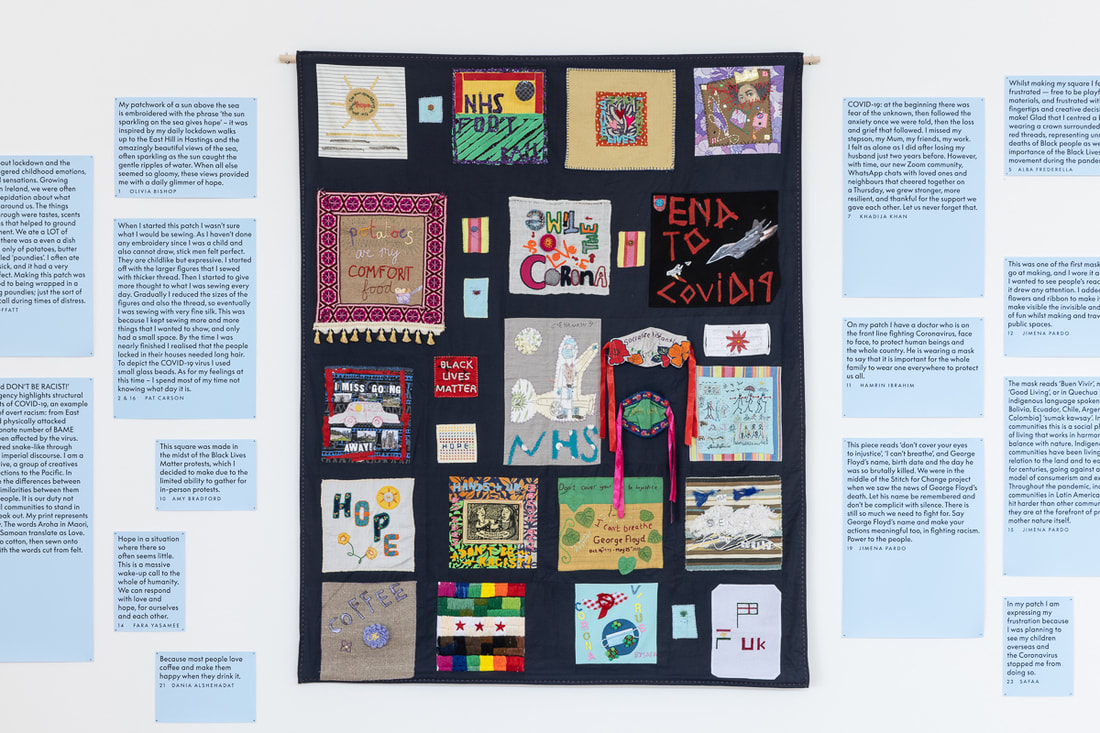

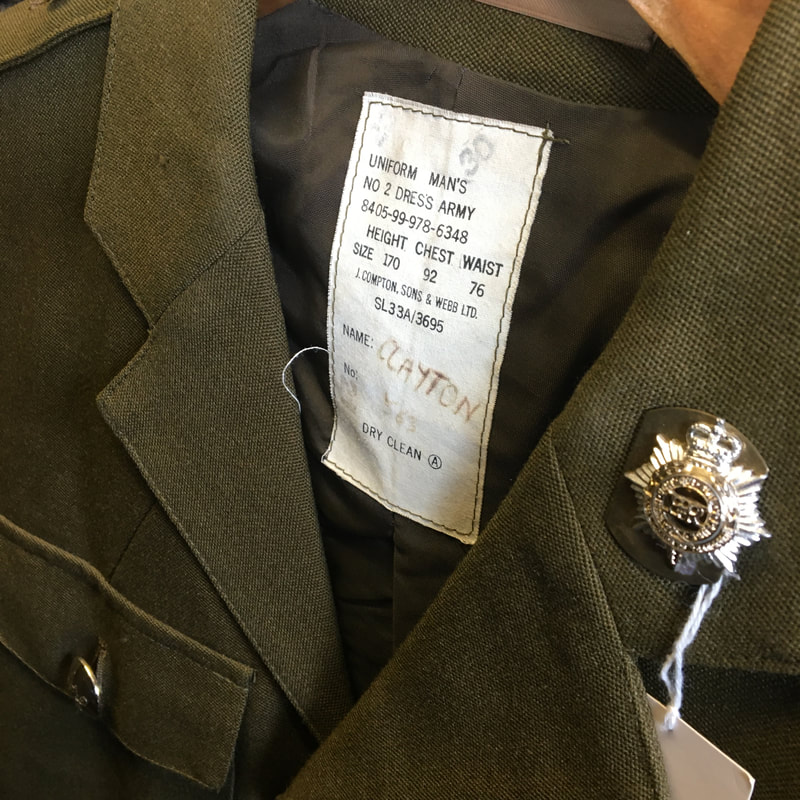

The book #ŽeneBiH is an artistic, activist and research initiative that is comprised of biographies of over 50 BiH women who have broken stereotypes and advocated women’s rights and emancipation. https://zenebih.ba/about-the-book/ The work conducted in Sarajevo was part of the Bandage Me Better project. Bandage Me Better: a textile project that binds, connects, heals It draws heavily on the sacred value of the items that support us in the everyday; the things that help us, heal us, and nurture us on our journey. We can feel deeply connected to such objects and find solace in them during times of sickness and adversity. A few weeks ago the exhibition All In The Same Storm: Pandemic Patchwork Stories opened at De La Warr Pavilion after months of hard work. I was one of two artist facilitators on the project; I learned much from my colleague Jimena Pardo who brought her in depth knowledge of the Chilean Arpillera movement that inspired and informed how we shaped the project. www.dlwp.com/exhibition/all-in-the-same-storm-pandemic-patchwork-stories/ I’ve written about the sessions that we led on Zoom in a previous post. What struck me most about the experience was how much everyday life became the stuff of art, culture and historical significance. We marked the time spent in a pandemic by commenting on, stitching about and mulling over what sometimes seemed otherwise mundane – that we needed coffee to get through the day, that we were bored, isolated and struggling with face masks. Using up fabric scraps to create patches for the final piece reignited a long kindling obsession for thrifted clothing and other pre loved domestic textiles. As soon as restrictions allowed, I’ve been feverishly rummaging through second hand and vintage clothing shops. It’s not just that I love a good bargain – although I do! It’s the sense of story that moves me when I handle cloth that I know has lain in someone else’s hand, caressed someone’s skin. The connection of me to the past through this garment makes me tingle with interest and excitement; the knowledge that I do not stand alone and isolated in time, but tangled up with so many other souls in the rich tapestry that is our existence. Sometimes I’ve stumbled upon things that have been extra moving – a row of military uniforms from the era of World War 2. One of the jackets had the owner’s name written on the label. Clayton’s jacket had been made by J Compton Sons & Webb who manufactured uniforms between 1930 and 1978. I wondered what had happened to Clayton and why his jacket was in such pristine condition, hanging in a shop in St Leonards on Sea. I have found myself collecting vintage nightdresses, wondering whether their owners have passed on or just given up the nightie for a more modern pair of pyjamas. A nightdress that I wore whilst pregnant has joined the collection and I gaze at them hanging in my studio – wondering whether there is a project stored up in their threads. One of Paddy’s vests, aged 4-5, has joined it; after dyeing it with red cabbage I’ve started stitching on top of it.

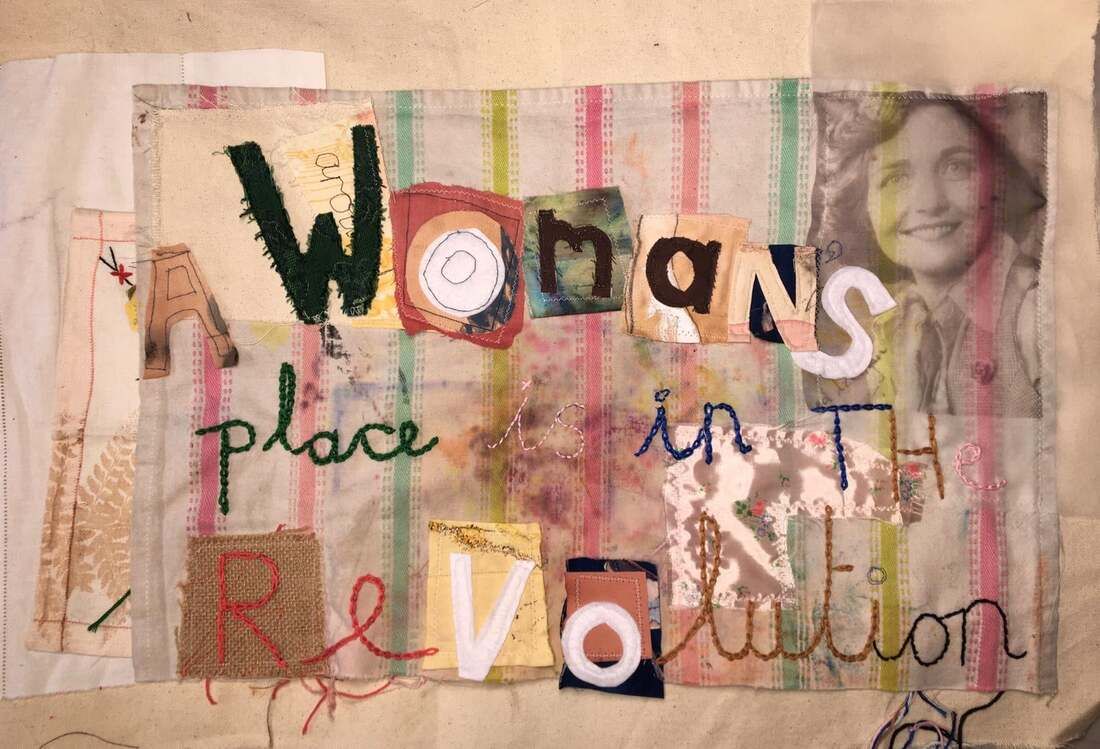

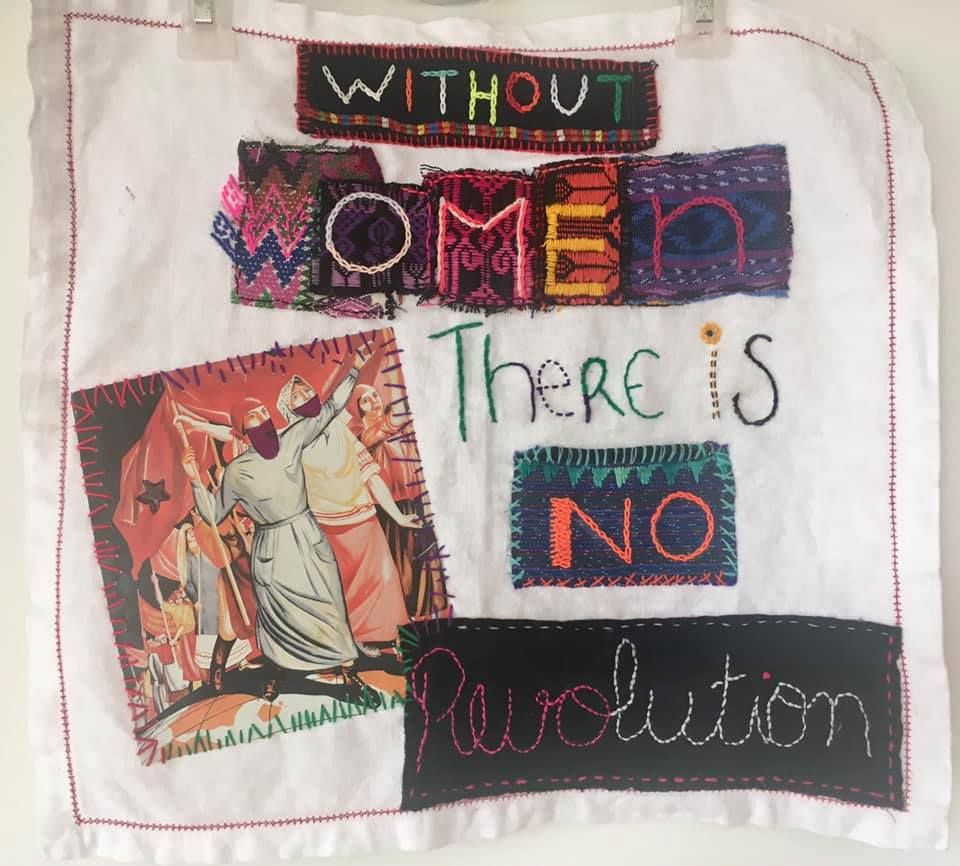

Does every textile have a secret life? Consisting of the imaginations, yearnings, hopes and memories of those who’ve handled it? All In The Same Storm runs until 5th September 2021. There is a panel discussion: www.dlwp.com/event/stitch-for-change/ As I write this, I received my first Covid vaccination an hour ago at a huge makeshift vaccination centre in Hastings. It seems like the beginning of the end of one long and winding road. It’s no secret that the Pandemic has had a huge effect on my life - like a kind of slow burning rocket going off. I’ve been plunged into exploring my inner world, delving deep into my personal buried trauma, but also reflecting on the collective pain of my country of birth and my familial ancestry. My Mum and I got into genealogy over recent months and uncovered a world of complex and meandering family life; one that’s been hoarding secrets of illegitimate children, religious conversions, ships to America and even a silver medal presented by the King of Sweden. It turns out that I am in equal measure Protestant Scots Irish, English and Catholic Irish. My Great Great Grandfather and Mother converted to Protestantism because they had a child out of wedlock and we believe that their only option was to be married by the Protestant church. My Great Grandmother (the one who married said child out of wedlock) also hailed from a Roman Catholic family – again converting to Protestantism to marry my Great Grandfather who was only Protestant by accident of birth. All this information confirms my long held belief that it’s preposterous to label anyone, and the labels are often useless, stifling constructs. The nature of life is nuanced and complex. People migrate, mix, mingle, love and birth new life in an unruly and uncontrollable fashion. No-one is fully anything and the world belongs to all of us. In reality there are no countries, no religions, no customs or faiths. There is only the ribbon of breath that we draw in and out of our chest each moment. Contemplating my Great Grandmother and Great Great Grandmother, the decisions they faced and the hardships they endured, has made me feel deeply connected to my place in an intertwined history. This has led me to reflect on women across Northern Ireland as a whole. I’ve felt able to reclaim Catholic heroes like Mairead Maguire, who has worked tirelessly for peace over the decades, awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1976. For years, I felt that Mairead didn’t stand for people like me – that by being labelled a Protestant I automatically fell on the ‘other side’ to her, whether I wanted to or not. That if she was speaking out, it was not speaking out for me. It feels deeply cathartic to reclaim all of my deeply Irish ancestry and the depth of that experience; from conflict and colonialism to poetry and pain. I am no longer separated from the myriad of influences that shaped me. I made ‘Reclaiming Mairead’ as part of a series of Stitch For Change sessions facilitated in tandem with Chilean artist Jimena Pardo, hosted by The Refugee Buddy Project in Hastings. We worked for four weeks in the run up to International Women’s Day helping women to make small banners and bandanas (panuelos) as worn by Latin American feminists, using reclaimed textiles from our everyday life. As always, Jimena taught me so much about identifying a colonialist past through texts such as Paulo Freire’s ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed’. I realise with a releasing awareness that the Troubles were not so much of a Protestant and Catholic issue as a deeply Patriarchal Colonialist issue. I’ve always loved the textiles of everyday life; from bandages and bedding to doilies and dishcloths. I adore the patina like surface that results from years of use and washing, perhaps because it draws me back to an almost nostalgic remembering of the grim and grey stained life we led on the Atlantic coast. I come from a long line of textile workers; my Great Grandparents and many of their children were involved in the linen industry, weaving cloth at Gribbons factory in Coleraine. My Nana was a dexterous seamstress, taking in jobs from her local community such as making curtains and adjusting hems – the stitching of everyday life. I remember being in awe of two particularly colourful bridesmaids dresses she made for my aunt’s wedding, saddened that I was not destined to wear either. It felt apt that Reclaiming Mairead started life as a much used, washed and stained tea towel from my own kitchen. I felt a loss at the lack of a radical feminist movement in Northern Ireland, but stumbled across the story of the Women’s Coalition in the documentary Wave Goodbye to Dinosaurs, a story that I had shamefully known nothing about until recently. I don’t ever remember women being any part of the political performances, but felt a thrill of hope when I heard about the coming together of women from across the divide. They successfully formed a political party in the space of six weeks and garnered enough votes to ensure that Monica McWilliams and Pearl Sagar were seated at the Peace Talks in 1996 – the only women sitting with 106 men.

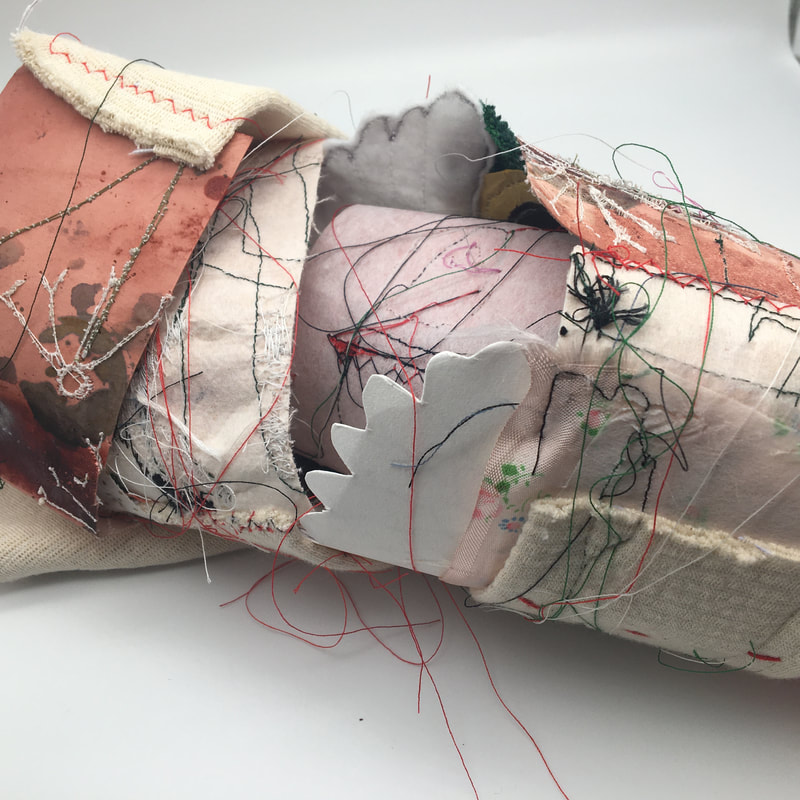

Of course they did I mused, because women in Northern Ireland have been quietly organising peacefully and successfully in their communities and families throughout the decades of the Troubles. Keeping their children educated and out of trouble, forming bonds via women-led cross community projects, and generally being the much needed glue of family life. Because that’s just what women do. I've always loved bandages; their soft, unbleached colour and supportive texture. Bandages are our attempt to make things better, wrap up, swaddle, contain, nurture, heal. As 2020 draws to a close, it seems pertinent to reflect that it has been a year to remember in so many ways; challenging, dark and filled with shadow, yet pregnant with opportunity for deep healing as old traumas have been triggered and brought to the fore. Many of us have keenly felt our vulnerability and lack of control for the first time in our lives, and coped with this by using all manner of 'bandages' that held and supported us during this period. By gardening, baking, painting and helping our community, we made meaning of a situation that otherwise seemed so fruitless. I've been creating Bandage Scrolls featuring Goddess Women; to me they look equally beautiful hanging long and unfurled, or wrapped in on themselves, featuring mainly their reverse and tatty sides. Bandage Scrolls feel like they contain something precious and tender of our personal stories, and making them has certainly assisted me in the process of breaking and mending that I've experienced throughout 2020. The global trauma has plunged me into old memories - my history brought to the fore in a stark and unavoidable fashion. I've noticed during the Pandemic the desperate scramble to organise, dictate rules, control and gain power over the virus - a struggle for control that becomes ever more elusive as Covid mutates and nature continues to envelop us in the way that she chooses.

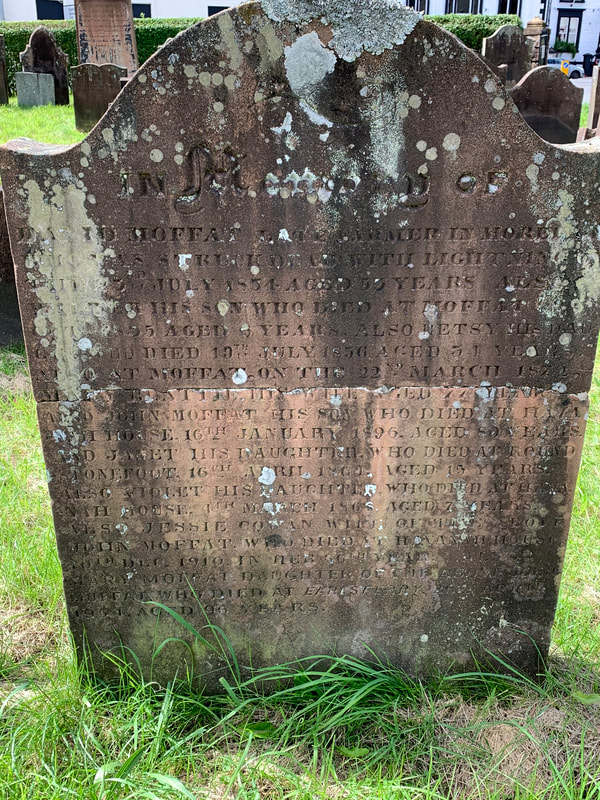

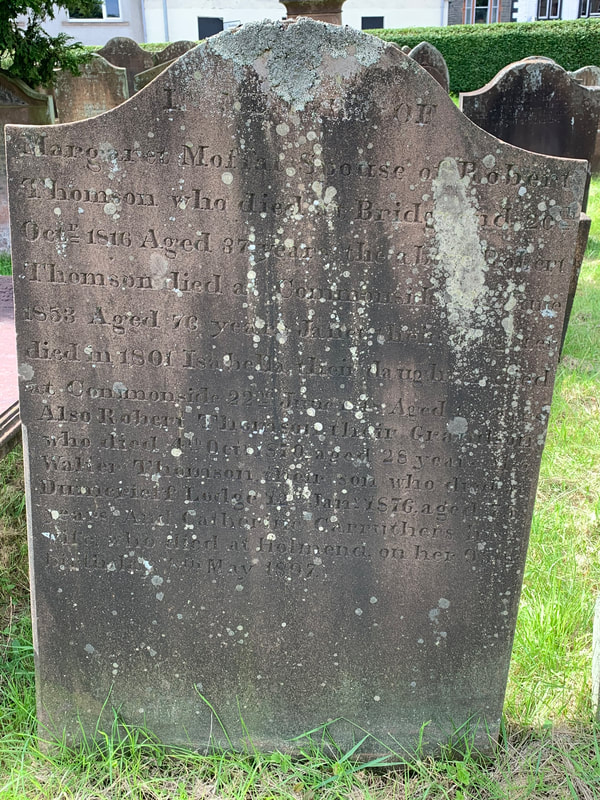

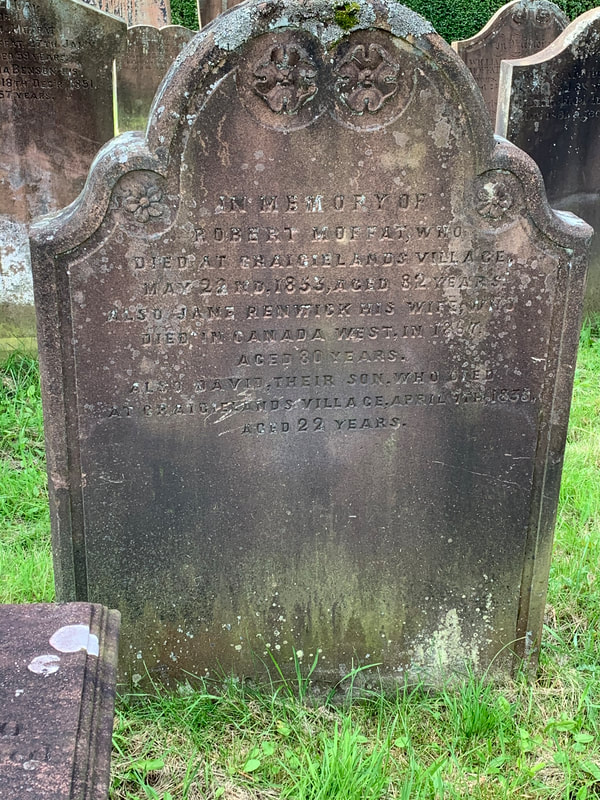

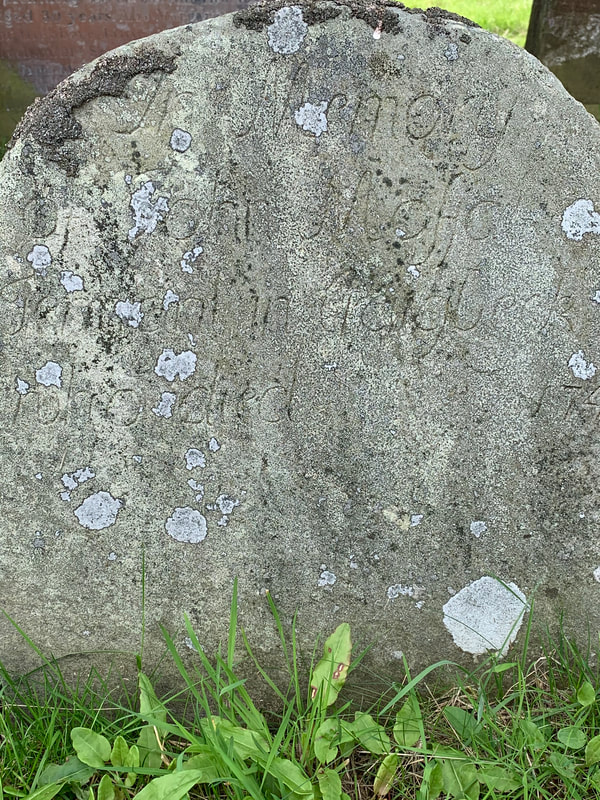

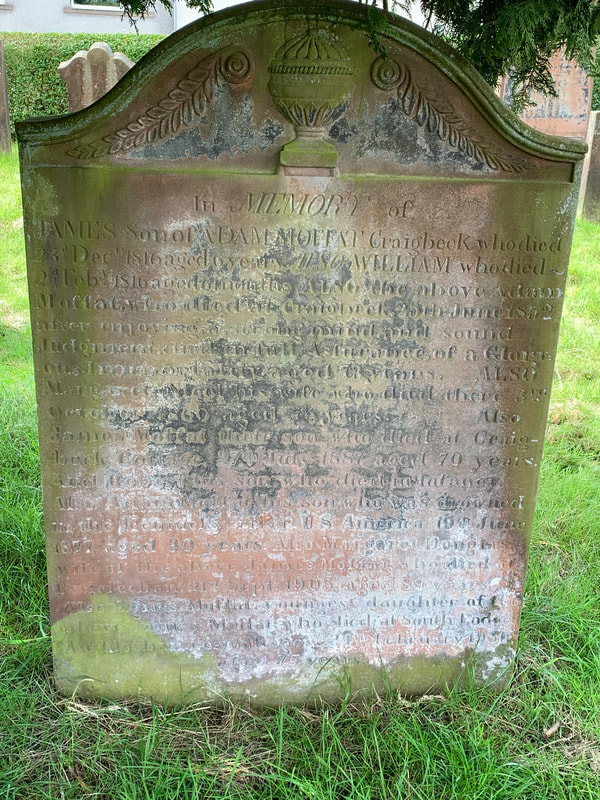

I'm struck by memories I have of being told about apartheid in South Africa, and my own experiences in Northern Ireland, where the powers that be attempted to organise blacks, whites, Protestants and Catholics. Of course, nature would not have it. Facing a multitude of people who would not fit neatly into their boxes, the South African government finally devised a water tight test to ascertain the category in which an individual belonged. By placing a pencil in a person's hair, they knew they were white if it fell out, and black if it stayed in. It seems amazing to our modern sensibilities that things got this desperate in the minds of adults who were in charge of a nation. Perhaps all this is a lesson in letting go and sinking into the stretchy bandage of life. We will never control it and we don't need to. Lockdown and the Pandemic has been the most surreal time I’ve ever lived through; in equal parts distressing, wonderful, and above all a steep learning curve. The role of art and nature as tools for healing are the subject of this blog; and I note that both have been used heavily during Lockdown as coping strategies by many. It seems that in time of great distress we turn to these things for comfort, expression and solace. I managed to take the time to do some online Peace Education with Quakers and really got to know about my own inner conflict, connecting with that part of me that wants to stand at attention like an aggressive sergeant major. An aspect of myself that strives for constant results, scornful of process and never allowing time to relax into the subtleties and nuances of my relationships and art practice. My appetite for greater understanding whetted, I attended a life changing seminar online that was presented by Professor Siobhan O’Neill, hosted by Ulster University and entitled ‘The Trauma Informed Approach’. In it Siobhan discussed trauma as a collective and intergenerational experience in Northern Ireland, touching on how trauma was passed around our society via poverty, childhood adversity, alcoholism and substance misuse, resulting in a huge proportion of the population being affected without witnessing anything obviously Troubles related (such as gunshots or an explosion). I thought long and hard about my Dad’s alcoholism and how this had a profound effect on me in our unhappy home. Memories of my uncle, a prison officer, being on an IRA hit list; checkpoints with heavily armed soldiers staring out of their armoured vehicles being a completely normal part of everyday life; our town being bombed so heavily that most of the centre had to be rebuilt; all of us segregated and the first question anyone wanting to know was ‘are you a Catholic or a Protestant?’ I’ve felt simultaneously weighted and relieved by these realisations, and noted that I need to continue to ‘make meaning’ from what has happened in my life – a point stressed by Professor O’Neill as the main way to recover from trauma and make sense of what can sometimes seem senseless. You can watch the seminar here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=cwDi0Q34g6M I therefore leapt at the chance to be involved in the project Stitch For Change, the brain child of Rossana Leal, the director of The Refugee Buddy Project. Rossana herself is a refugee from Chile who arrived to live in Scotland when she was eight years old. She understands more than most what it is like to flee from a situation that is dangerous and traumatic, having left her native country to escape the Pinochet dictatorship that saw thousands being disappeared, detained and killed. Stitch For Change envisaged the completion of a Pandemic Patchwork Quilt, with exquisitely hand embroidered squares being stitched by Sussex based refugee families who are being supported by the project, along with anyone else who wanted to get involved. Participants were asked to stitch stories of their time during the pandemic; anything could be included. We gratefully received deeply moving stories of individuals’ displacement and other light hearted reflections on how coffee has been an integral part of making it through lockdown. The project has been heavily influenced by arpilleras from Chile; their history and techniques were taught to us by fellow facilitator and artist Jimena Pardo, also hailing from Chile. We learned how Chilean arpilleristas would make their deeply moving pieces of textile work to express the pain of losing a loved one, using scraps of fabric and burlap backing. Jimena runs a collective called Bordando por la Memoria; they state: 'Our aim is to make collaborative textile pieces that highlights the need for justice and to keep alive a part of history that in Chile today is being systematically eradicated.' You can find out more about the collective here: www.facebook.com/groups/155475955130949 You can find out more about Jimena’s own deeply moving story here: www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w3cszf07?fbclid=IwAR3ajdAdMPwUnigKDWe_Z3czkagidPTdPjOIeGFyS9guQkYv5U4kzCvAM7M We ran two weekly Zoom sessions and initially I was worried about the number of attendees, scared that we wouldn’t have enough to make the project a ‘success’. Rossana, completely unflappable and entirely trusting in the process and the richness of the engagement, taught me to trust that it was a matter of quality rather than quantity. I learned a lot about the subtlety of important change and growth in individuals, and the necessity of examining project results in depth with an eye on individuals’ experiences as opposed to how many people had attended. I had a tendency to focus on the latter in the past, feeling the need for numbers and results in order to prove the validity of my work. I’ve had a deep shift in my awareness that it’s unethical to view a human being only as a number or statistic – and this type of number crunching is a skewed way of evaluating work amongst humans. I’ve also realised that activities that can look rather unimpressive on the surface can actually be implementing profound changes in participants and that simple activities that are well delivered within a nurturing space are far more important than a project that screams with bells and whistles but that lacks space for reflection and connection. I was moved by the positive response of participants – they seemed to glean a great deal out of the fact that we were simply a consistent, reliable presence in what was an otherwise tumultuous time. Even if they didn’t manage to attend every session, they were very much a part of the process and were held by the space even when they weren’t in it. I noticed that this increased my own capacity for compassion towards the group and myself, which has significantly benefited my art practice. We are now in the throes of creating quilts from the individual patches with the help of textile artist and master quilt maker, Jane Grimshaw. The quilts are due to be displayed at De La Warr Pavilion at the end of the year alongside a programme of events. Above all, this beautiful project has brought home to me with resounding clarity that healing is my only purpose: divide is conflict and integration is harmony, and this echoes in all areas of life from the inner to the outer. There is an academic term ‘Post Traumatic Growth’ which essentially means that you can be better for the things that you’ve been through. May we all work through our struggles and know the deep satisfaction of this growth. Lockdown has been and (sort of) gone, and we are now living in a new kind of 'normal'. The pandemic has, of course, changed absolutely everything - including my relationship with myself. So it only stands to reason that it has begun to considerably shape my art practice. This blog originally started out as a reflection on how nature can sustain and heal; never have I felt so held by the landscape around me as during these troubled times. I need to be in it like I need to drink water - the fear and uncertainty has driven me to bathe in nature's restful arms and connect with her ever changing light every day. I feel much more thoughtful about everything I do; I'm slowed down and picking through the pathway of my life much more carefully and with greater attention to the subtle detail that lies everywhere along the road. I still see conflict everywhere. The internal battles we fight as we struggle to attain that elusive sense of inner peace. The wars that rage in the name of justice. Is this just an inevitable part of our human condition? More and more I see the nuances - we are neither simply good or bad, the oppressor or the oppressed. We are everything. It's just what we choose to reflect upon most that ultimately shapes who we become. This summer we decided to abandon plans to jump on a flight to somewhere exotic and follow that subtle, dusty road north to the Scottish Highlands, reaching Loch Lomond, Ben Nevis and the Isle of Mull; a part of our island almost outrageous with moody beauty. On our route back home I managed to pay a mini pilgrimage to Moffat; the town undoubtedly the seat of my Scottish ancestors. I am a result of the Scottish Plantation, Scots Irish, a combination that regularly made me wince in the past as people would proclaim we were 'not proper Irish', and inevitably connect us with Protestantism, Unionism and the role of oppressor in the Troubles. For some time I considered that I had no right to sadness about the conflict that still rumbles in Ireland - surely I could lay no claim to sorrow about a situation that I must have benefited from? Now I know that no-one gains any advantage in war, killing, oppression and deep division. It may look like some have an upper hand from certain vantage points, but none of us know peace until we all know peace. We all have the right to grieve the deaths of people killed in violent action, no matter whether we knew them or share the labels that others have placed upon us. A life is a life. We are all one people under one sky. Gravestones bearing the name Moffat in the town's cemetery

|

AuthorAbout Northern Ireland; conflict, walls & resolution Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed