|

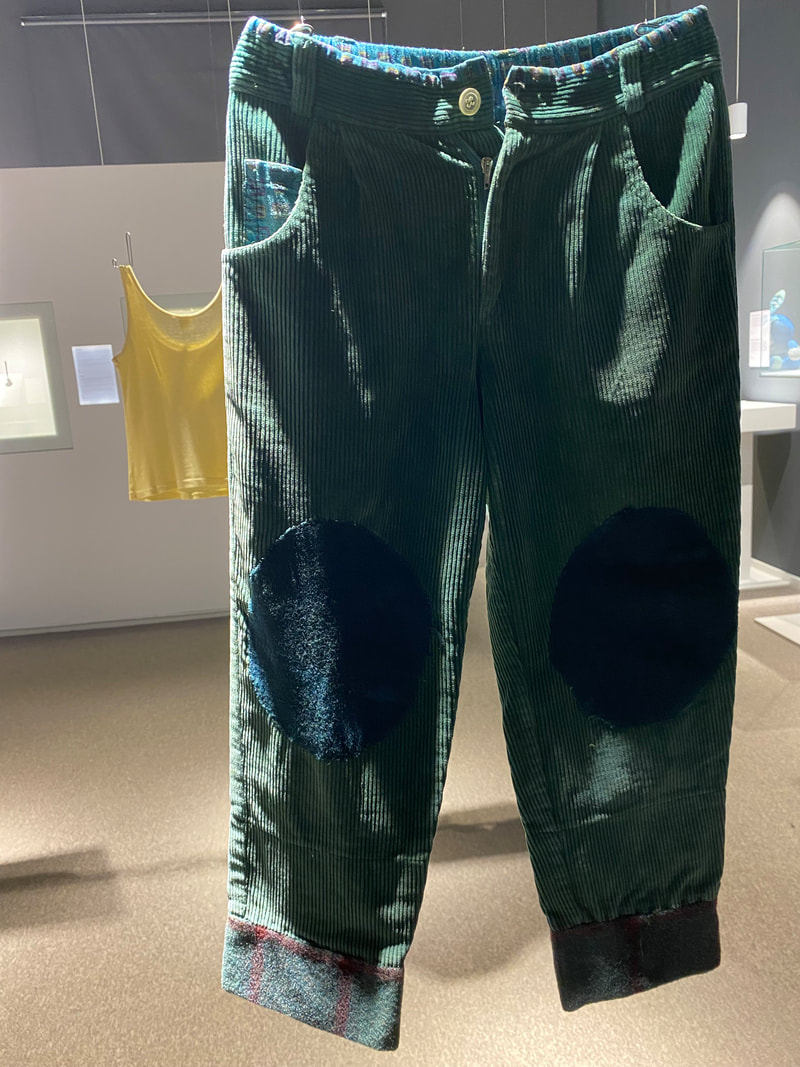

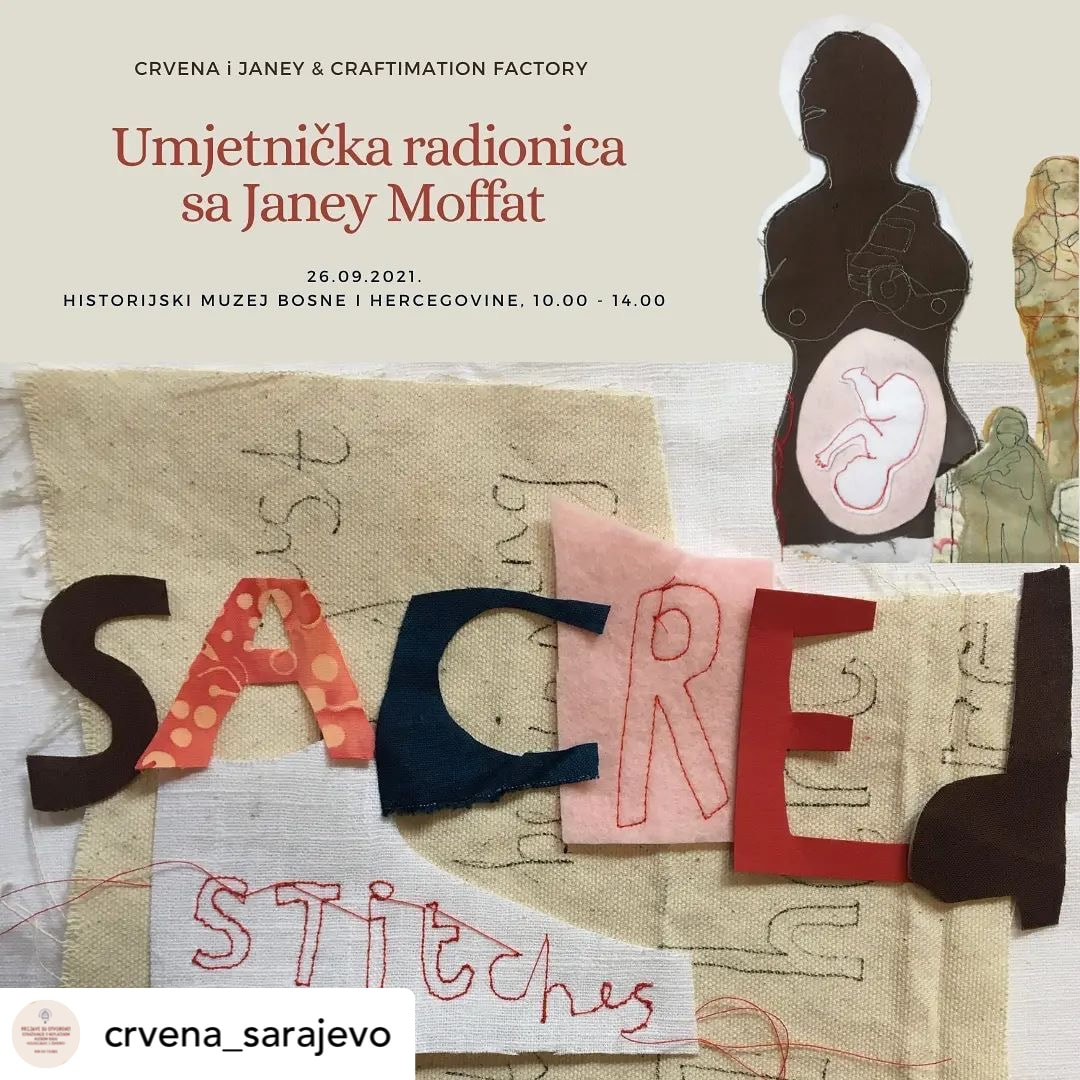

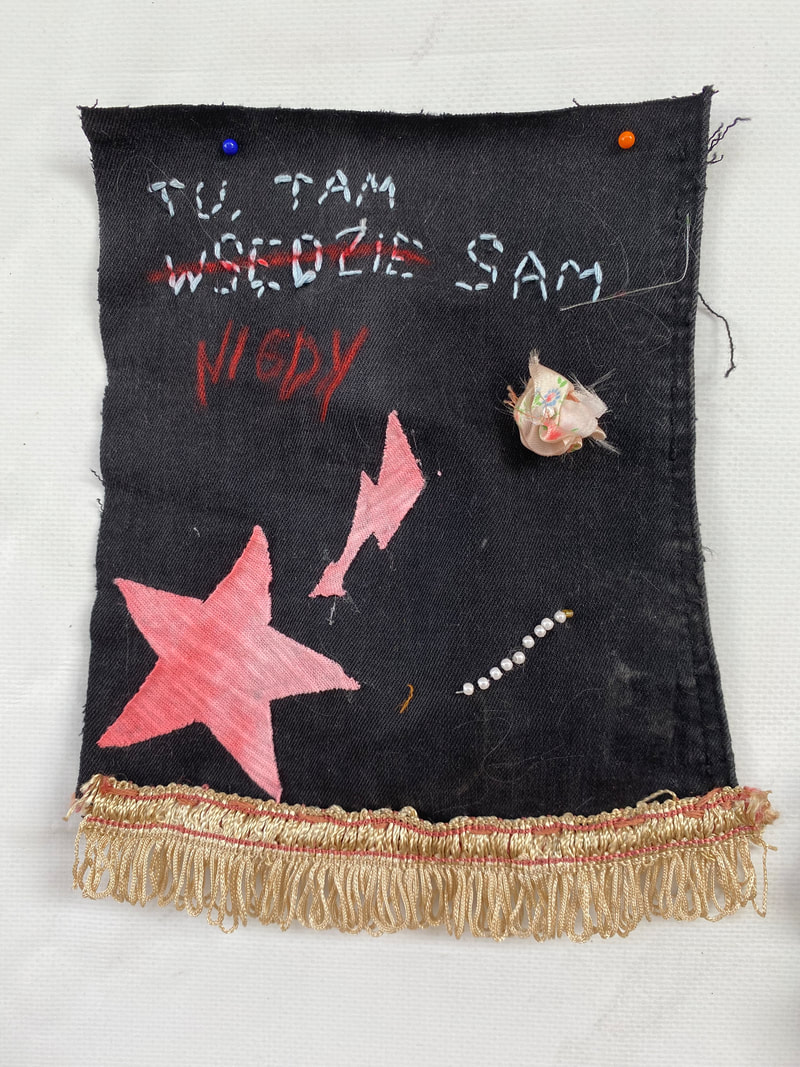

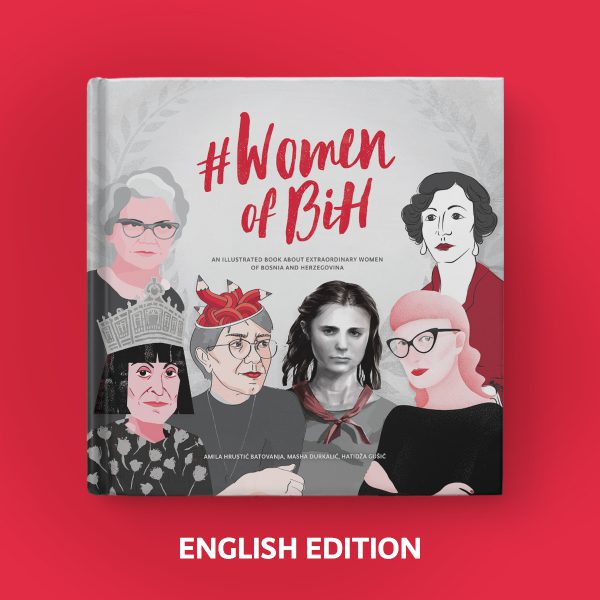

The Bosnian War; a long, complex, and ugly conflict that followed the fall of communism in Europe. In 1991, Bosnia and Herzegovina joined several republics of the former Yugoslavia and declared independence, which triggered a civil war that lasted four years. Bosnia's population was a multi-ethnic mix of Muslim Bosniaks (44%), Orthodox Serbs (31%), and Catholic Croats (17%). The Bosnian Serbs, well-armed and backed by neighbouring Serbia, laid siege to the city of Sarajevo in early April 1992. They targeted mainly the Muslim population but killed many other Bosnian Serbs as well as Croats with rocket, mortar, and sniper attacks that went on for 44 months. As shells fell on the Bosnian capital, nationalist Croat and Serb forces carried out horrific "ethnic cleansing" attacks across the countryside. Finally, in 1995, UN air strikes and United Nations sanctions helped bring all parties to a peace agreement. Estimates of the war's fatalities vary widely, ranging from 90,000 to 300,000. To date, more than 70 men involved have been convicted of war crimes by the UN. – Alan Taylor, The Atlantic Despite the pandemic still writ large, and with no small amount of trepidation, I recently deliberated on whether I should rebook a work and research trip to Sarajevo that had been planned before Covid struck us. With travel rules constantly morphing, I dreaded the prospect of being stranded in a dodgy hotel hundreds of miles from home, yet a small but loud part of me insisted that I needed to get back out into the world and embrace it. On 24th September I flew to Sarajevo via Vienna and landed exactly on time and with no hitches whatsoever. I had yearned to visit Sarajevo ever since a family holiday to Croatia that saw us taking a day trip into Bosnia & Herzegovina, taking in the sights of the beautiful city of Mostar. I was captivated instantly by a place that was worn around the seams, dishevelled by conflict yet boasting great pride and beauty. Riddled with scars and carrying a silent sorrow in its soul, I recognised at once a country that had endured yet survived. I adore this kind of worn out, harrowed loveliness way more than any ‘perfect’ tourist destination. Because it’s in this dilapidation where great stories live. I was lucky enough to connect with Crvena, a feminist organisation based in Sarajevo who had agreed to host me as I facilitated a textile workshop. They had organised for me to work in a sunny outdoor courtyard at the rear of The History Museum of Bosnia & Herzegovina, where I was surrounded by the leftover machinery of war; all sorts of cannons and other killing paraphernalia sat lazily in the sunshine whilst we worked around them. The evening before the workshop I met with the irrepressible Andreja of Crvena; she had given birth to a baby boy only two months prior yet was energetically organising and promoting the workshop. She took me to Caffe Tito, a nostalgic reminder of life in former Yugoslavia under President Tito, with photos and other objects from the socialist period. We chatted and swapped experiences of life as women, the searing inequalities that we face in our roles as mothers, how conflict shaped the lives of women. She told me how she and her mother had been forced to leave BiH as refugees for the relative safety of Croatia, the grief in giving up their comfortable life in Sarajevo to live in substandard conditions in order to be safe. The next day, with Andreja translating, the workshop went smoothly - me learning way more than any of the participants. They told me they were communists, and elaborated on how strong the feminist movement had been during the time of Yugoslavia. Andreja had previously devoted her time to putting together a small permanent exhibition that was housed in the museum. It displayed, along with other items, copies of the radical ‘New Woman’ magazine that had been published during the period. After the workshop I gazed at the items, wanting to know so much more of their story. Some of the participants at the workshop had been really young, born long after Yugoslavia had broken up and rearranged itself into new countries, long after the most recent war had raged. Yet they burned with Yugonostalgia and a passion for a time that they had never known. I couldn’t blame them. Capitalism has hardly brought us untold joy, so why wouldn’t they look to something else? I turned the idea of communism and its potential benefits over in my head. It was certainly food for thought. Read more about Crvena here: crvena.ba/ Learning about the nuanced and complicated history of the Balkans was therapeutic for me; it ensured that my own troubled story in Ireland felt less isolated and strange. I deepened the conversation by connecting with a couple of other people; a journalist called Orhan who had been a young adult during Yugoslavia, and who had fled to Turkey during the conflict, and a guide called Adis who was born in the last year of the war. Adis took me all over the city and I glimpsed the Tunnel of Hope, constructed between March and June 1993 during the Siege of Sarajevo, allowing food, war supplies and humanitarian aid to make its way into the city. He showed me Sniper Alley and the still pock marked buildings blighted by gunshot wounds, but also the dilapidated bobsleigh track made famous by the 1984 Winter Olympics (who could forget the world famous performance by Torville and Dean?), now covered with street art and political messages. And how did Orhan remember the period? The communism of Yugoslavia had failed he stated pragmatically, feeling that there had been a certain inevitability to it all, pondering over the Ottoman invasion centuries prior and reflecting how the conversion of many to Islam at this point had continued to influence tensions in the region hundreds of years later. Later, back at my AirBnB, I learned how women had formed their own resistance during the war by donning their best clothes and make up, even when they were forced to walk down Sniper Alley. Their attitude was one of defiance – if they were going to die, they were going to die dressed in their best. I watched footage of Miss Sarajevo on YouTube; contestants of the beauty pageant held in the midst of the besieged city had carried a huge banner stating ‘Don’t Let Them Kill Us’, with the moment immortalised in song by U2 and Brian Eno. I marvelled at how the women had held together the threads of a normal life in the midst of chaos and destruction, as I know women do the world over. Holding things together for their children, their wider families and communities. On the final day of my visit I stumbled across the book Women of BiH in a tiny store placed along a side street. I immediately purchased it, feeling instantly that I needed to know more about these pillars of strength, knowing that I would draw on their fortitude and grace in times of need.

The book #ŽeneBiH is an artistic, activist and research initiative that is comprised of biographies of over 50 BiH women who have broken stereotypes and advocated women’s rights and emancipation. https://zenebih.ba/about-the-book/ The work conducted in Sarajevo was part of the Bandage Me Better project. Bandage Me Better: a textile project that binds, connects, heals It draws heavily on the sacred value of the items that support us in the everyday; the things that help us, heal us, and nurture us on our journey. We can feel deeply connected to such objects and find solace in them during times of sickness and adversity.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorAbout Northern Ireland; conflict, walls & resolution Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed